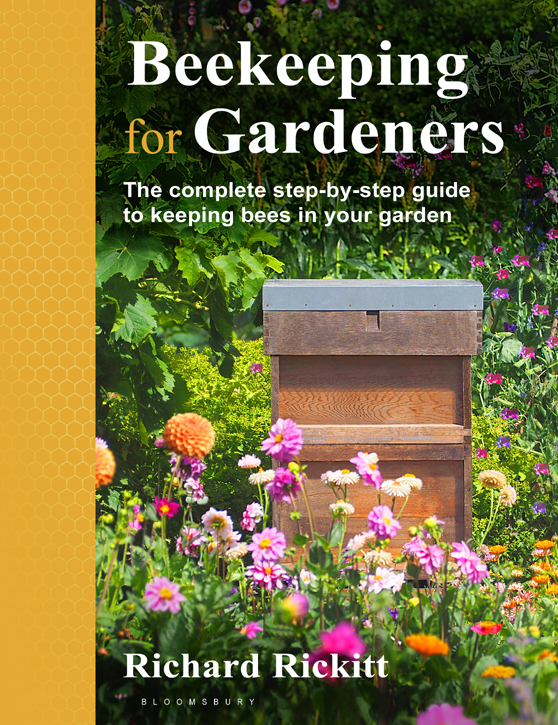

This beautifully illustrated book provides a comprehensive gardener’s guide to sustainable beekeeping. It reveals the pleasures and benefits of keeping bees in gardens of all sizes in both rural and urban areas, explains the practicalities of this widely enjoyed hobby and lists the top performing plants that will help your colony thrive. Beekeeping for Gardeners also discusses the hobby of beekeeping within the wider environment and questions how it can meet the needs of all species of pollinators, as well as it’s potential contribution to the local ecology.

Richard Rickitt is an award-winning author as well as co-editor of the UK’s best-selling beekeeping magazine BeeCraft. He has been an avid beekeeper for over 20 years, maintaining numerous hives for both commercial and private clients as well as his own, looks after the bees at the National Arboretum, and teaches beekeeping courses across the UK as well as abroad.

Richard Rickitt is an award-winning author as well as co-editor of the UK’s best-selling beekeeping magazine BeeCraft. He has been an avid beekeeper for over 20 years, maintaining numerous hives for both commercial and private clients as well as his own, looks after the bees at the National Arboretum, and teaches beekeeping courses across the UK as well as abroad.

Richard recently took the time out of his busy schedule to talk to about Beekeeping for Gardeners, including what inspired him to write a book aimed at gardeners, what the future of Honey Bees in Britain looks like and more.

Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about yourself and what prompted you to write a beekeeping book aimed specifically at gardeners?

I grew up on a Somerset smallholding, so my heart is in the countryside. I always loved wildlife and my bedroom was like a miniature Natural History Museum filled with bird’s nests, animal skulls and a menagerie of frogs, newts, caterpillars and anything else I could catch and keep. One day I peeked through a garden hedge to spy on an old beekeeper at work. The white hives, sparkling clouds of bees and puffing smoker seemed mysterious and magical. I suspect that I have a very romanticised image of the scene in my mind, although even now when tending my bees I am often struck by what a bucolic activity it can be. Later, I learned beekeeping at my secondary school which had an excellent rural studies department – I’m not sure if such things exist anymore, which is a terrible shame. I went on to work in film and television special effects, but after moving from London to Wiltshire about 18 years ago, I took up beekeeping again. I became increasingly involved in the beekeeping community, eventually becoming co-editor of BeeCraft, the UK’s bestselling beekeeping magazine, which is now in its 105th year.

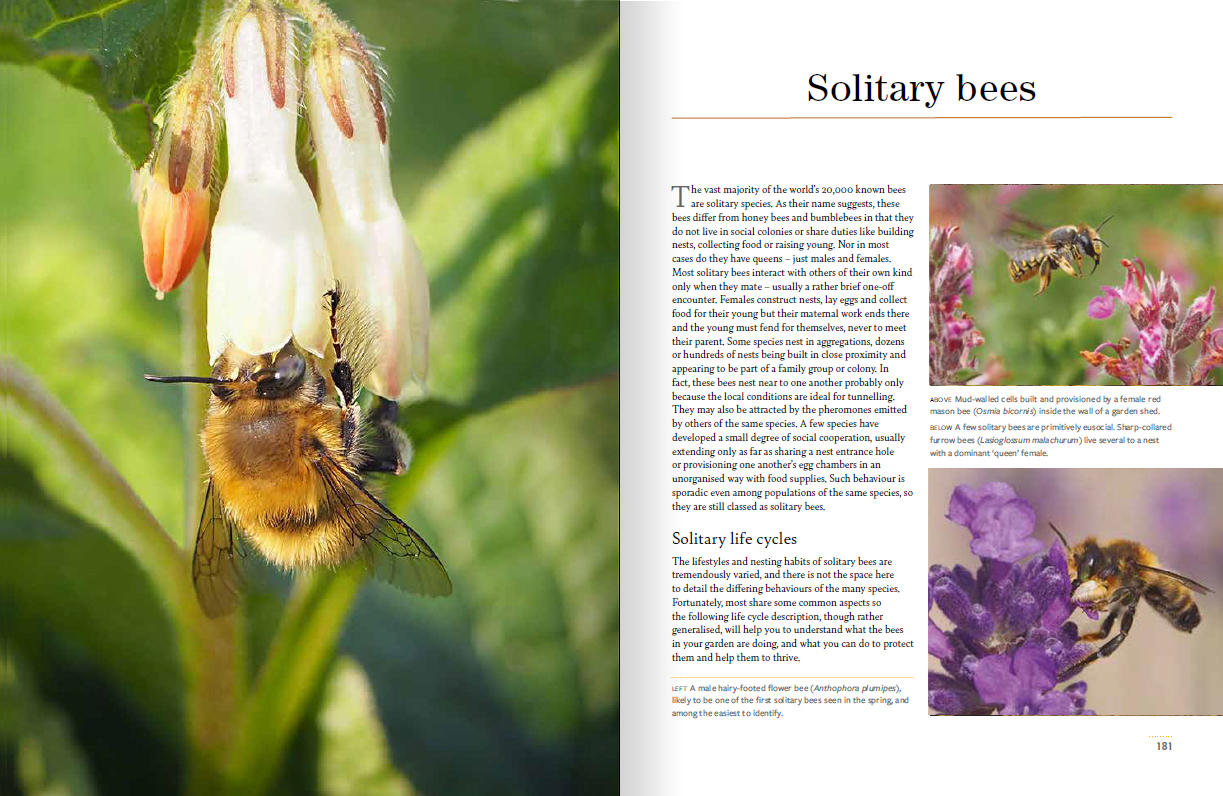

I wrote a book aimed at gardeners because many of the people attending my beekeeping courses are already gardeners and want to know more about the bees that they see visiting their flowers. By starting out as gardeners, new beekeepers are already doing one of the most important things that anyone can do for bees; providing them with the resources and habitats that they need. But sometimes a little extra knowledge and small changes in the way you garden can make a huge difference to the sustainability of your local bee populations. For example, some species of solitary bee depend on a single, specific variety of flower.

Keeping honey bees dovetails very nicely with gardening; it’s a seasonal activity done mostly in good weather in spring and summer. Time spent in the garden can be time spent tending both plants and bees, enjoying watching them develop and interact through the year. Gardeners enjoy choosing what plants best work in their garden and if you are a beekeeper there can be the added pleasure of planting specifically for bees and seeing them make use of what you have provided. There are practical benefits too; fruit and vegetable crops will be better pollinated, resulting in more and higher-quality produce. And, of course, there can be the reward of a crop of delicious honey and even wax with which to make candles or cosmetics. Like gardening, beekeeping is a lovely hobby to share as a couple or family – each person often finding their own areas of interest, and sharing the work, discoveries and pleasures.

So, my book is for anyone who loves gardens and is interested in learning about and helping bees of all kinds. They might want to create a beautiful garden with the most appropriate plants, habitat and nesting opportunities for wild bees, or take things further and keep a hive or two of honey bees.

I really liked how the book provided not only a comprehensive guide to beekeeping on a small scale but is also an exceptional resource of information on growing flowering plants and creating habitats for bumblebees, solitary bees and insects of all kinds. Do you think traditional beekeeping advice has tended to be very focused on the Honey Bee itself with less of an emphasis on providing the habitat it requires to thrive?

Beekeepers have always very carefully noted which plants flower near their bees, as well as the quality and quantity of honey that their bees produce as a result. However, the presence of such resources has generally been taken for granted; the beekeeper only having to look after the bees while it was assumed that nature would provide the rest. Increasingly, because of habitat loss, climate change and pollution, the necessary resources aren’t always there. Today’s beekeepers therefore have to think not only about caring for their bees, but also about caring for the environment in which their bees live. That includes growing more of the right plants but also considering whether their bees might have a negative impact on the local environment and the other species it supports. Most beekeepers begin their hobby for environmental reasons and try have a positive impact.

How do you think beekeeping fits within the broader context of conservation, given that the honey bee is considered by some as not native to Britain and may spread diseases to or compete with other important wild pollinators?

This is a great question involving several complex issues, so I’m afraid it requires quite a long reply.

The first point is the erroneous but increasingly commonly held belief that the honey bee is not a UK native species. The oldest fossil of a true honey bee (Apis species) comes from Germany and is about 25 million years old. The distribution of such bees, along with all species of plant and animal, will have fluctuated drastically over the millennia in response to changes in geography, environment and climate. However, when the ice retreated at the end of the last ice age, some 10,000 years ago, what is now called Britain was still connected to the European continent. This allowed the spread northwards of animals and plants. Honey bees naturally live in tree cavities and undoubtedly would have spread into Britain as trees began to grow here. Then, when sea levels rose about 6000 years ago, Britain became an island. This is the cutoff point at which species already established and subsequently isolated here are generally considered to be native. That would certainly have included honey bees as well as the hundreds of other species of bumblebee and solitary bee that we now consider to belong here. So, I think there is no doubt that honey bees are in fact native. Indeed, there is archaeological evidence of the presence of honey bees in Britian dating back thousands of years. For example, the remains of venison cooked with honey were found in Bronze Age artifacts recently unearthed in Peterborough. There is no such archaeological evidence for the presence of any species of solitary bee or bumblebee in Britain at that time, although I wouldn’t question that most of those are also native. For more about the evidence of the honey bee as a native species, I would recommend reading an academic paper by Norman Careck of Sussex University.

Many of the bumblebee and solitary bee species found in Britain are also found on the continent and are considered native in both places. However, the honey bee, also naturally present on both sides of the channel, is currently claimed by a few people to be non-native in Britian. This contradictory claim only seems to have come about in the last decade or so and is perhaps partly because of a history of commercial importation of honey bees from the European mainland into Britian. Such imports have been made for three reasons; firstly, because in the early twentieth century many of our wild and managed honey bee colonies died as a result of a disease then known as the Isle of Wight disease – so much so that the production of pollinated farm crops was thought to be threatened; secondly, it was thought that the slightly different genetic traits of honey bees from elsewhere could be used to produce more disease-resistant and productive honey bees in the UK; and thirdly, because commercial beekeepers whose bees pollinate crops in spring often require new queens to replace those that have died over winter – and the British climate makes it impossible to raise new queens here until later in the season. The result has been an influx of honey bee queens from Europe. These bees are the same species as has existed here for thousands of years (Apis mellifera) but they have evolved into regional subspecies because of the slightly differing environmental conditions where they live. Honey bees living in Italy will experience a very different climate and flowering plants to those living in Scotland, for example. The result is that many of our honey bees now have a mixture of genes hailing from different places.

Some hobby beekeepers today are against the importation of honey bees and increasingly favour what are known as local bees. These are bees raised from colonies that survive and thrive in a relatively small geographical area, without the addition of new genetic characteristics from bees imported from abroad or elsewhere within the UK – they are ecotypes. The actual genetic makeup might be a mixture of all sorts, depending on what is already in an area, but studies have shown that, over time, the native genetic element tends to dominate. There are some areas of the UK where the genetics of local honey bee populations are very highly native. However, as climate change worsens, adaptability will be key to the survival of all species of animal and plant; it might be that genetic traits from imported honey bees are what eventually give our honey bees the ability to survive in unstable climatic conditions. In my book, I urge beginner beekeepers to buy new bees and queens from a local beekeeper who has kept the same bees in the same place for decades, these honey bees will probably be best suited to your area.

Now for the second part of the question, which is also complicated but I will try to keep things brief. There are several diseases that appear to be shared in one form or another by various types of bee. Research into these diseases, their effects and transmissibility, is at the early stages with very few definitive conclusions at the moment. One disease, called nosema, is a kind of fungus that affects the gut of a bee. This is found in both honey bees and bumblebees. It is thought that this first evolved in butterflies, and has since been passed on to bees, which can be spread from one species to another perhaps by sharing the same flower resources. One of the biggest threats to honey bees is the presence of varroa, a tiny parasitic mite that can spread various pathogens when feeding from the bodies of developing honey bee pupae. It’s not yet clear which of these pathogens can spread to other species of bee which are not in themselves hosts to varroa.

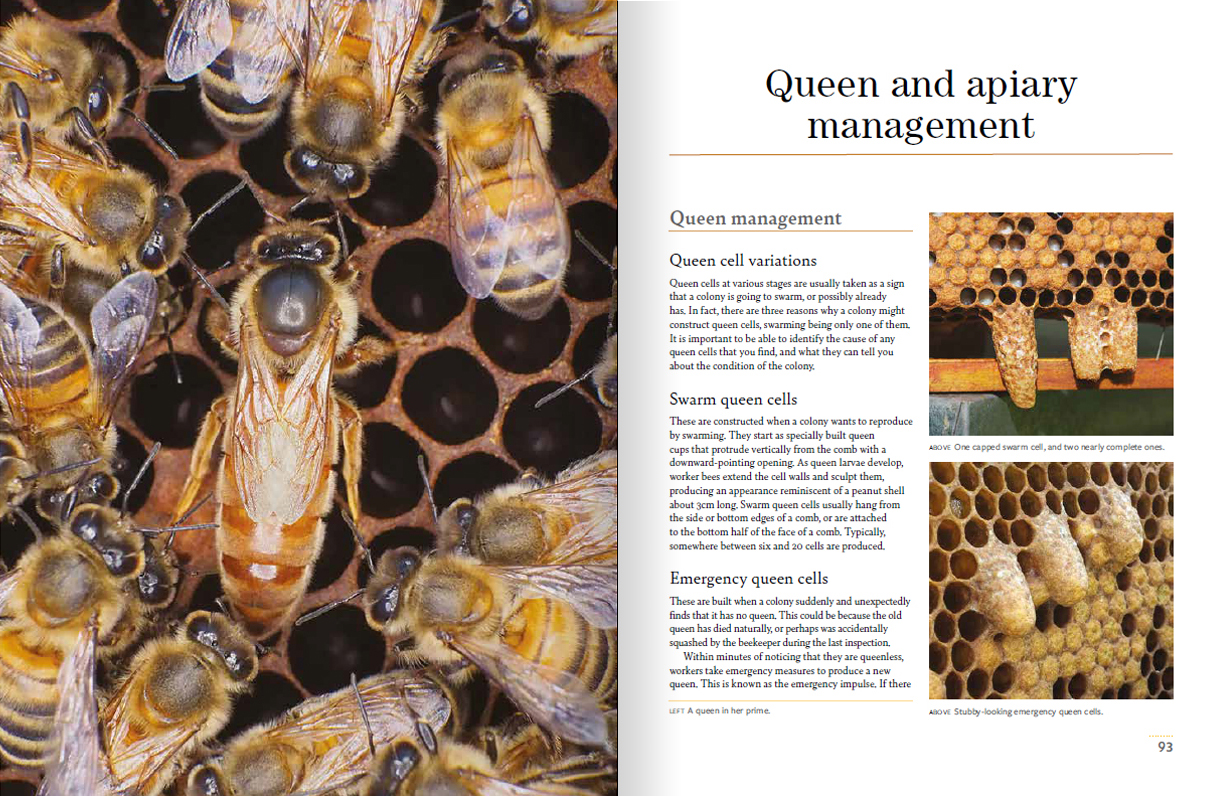

There are a lot of uncertainties, and it is by no means clear that honey bees are a significant disease danger to other species of bee, or the reverse. However, it highlights the importance of beekeepers fully understanding the biology and lifecycle of honey bees, and their diseases and predators. This will enable them to keep healthy bees that are better able both to resist diseases and minimise the chances of spreading them to other species. Reading my book is a good way to begin understanding how to keep healthy honey bees, and indeed if beekeeping is really for you. After that, I strongly suggest joining your local beekeeping association and signing up for a training course.

Finally, and referring to the first part of your question, you asked about where beekeeping fits into conservation more broadly. The fact is that because beekeepers generally do a good job of looking after them, honey bees are not currently under threat – despite being subject to many of the same pressures as solitary bees and bumblebees. There was a great deal of worry some years ago when huge numbers of honey bees died for largely unknown reasons, but those problems are now generally under control. We shouldn’t be complacent, however; there are still a great many threats to honey bees and the climate crisis poses lots of potential problems.

I consider honey bees to be the ‘gateway bee’. Many people who have never had a very close relationship to wildlife or the natural world are attracted to beekeeping as a fascinating and rewarding hobby – sometimes at first they don’t even understand the difference between honey bees and other bees. Once they are acquainted with honey bees, such people often want to learn more about the other species of bee, ultimately taking part in conservation measures and becoming bee ambassadors, spreading the word about the importance and fragility of bee populations generally and appreciating the importance of plant life and biodiversity in general.

Beekeeping within the UK appears to be a thriving pastime and, throughout the Covid pandemic in particular, it seems that many were inspired to take it up as a hobby. Could we reach a situation where we have too many beekeepers?

It’s thought that in the UK there are about a quarter of the number of honey bee colonies there were in the 1950’s, and far fewer than might have been present naturally a few thousand years ago – a natural density of about one colony per square kilometre is estimated by renowned bee scientist, Professor Tom Seeley. But although we may have fewer honey bees now, we also have a hugely degraded environment that is much less capable of supporting bees of all kinds.

There was a huge drop in the number of beekeepers and bee colonies in the mid-1990s, with membership of the British Beekeeper’s Association (BBKA) dropping to just 7000. When the media began to highlight the problems being experienced by honey bees, particularly due to so-called colony collapse disorder, the number of beekeepers began to rise again. As you say, numbers increased somewhat during the pandemic, too. Today there are about 27,000 members of the BBKA. That number seems to be levelling off and I wouldn’t be surprised if it has reached a peak. There are new beekeepers every year, of course, but people also drop out of the hobby at about the same rate as they join.

I think it is unlikely therefore that we will have too many beekeepers overall, but I do think that the distribution of beekeepers and their bees is a matter of possible concern. Beekeeping has become popular in large cities, and although suburban areas with their dense patterns of small gardens containing a wide variety of plants – not to mention parks, allotments and railway embankments – can provide plenty of bee habitat, city centres are often extremely poor places for supporting bees and other pollinators. The trend for putting beehives on top of city centre office buildings is highly questionable when there are so few flowering plants nearby. There are also a few rural areas with particularly fragile populations of rare bee species where it might be unwise to keep honey bees. A very high density of honey bees in any area could increase the chances of disease transmission – as discussed in the previous question. These are all issues discussed in my book.

Overall, I believe that thoughtful beekeeping is environmentally beneficial. Although you can place bee hotels in your garden and plant gardens to attract bees, there is nothing quite like learning about and witnessing the extraordinary lifecycle of a honey bee colony for opening people’s eyes, minds and hearts to the breathtakingly complex and beautiful natural history of bees and pollinators in general.

With constant monitoring in place for the arrival of pests such as Tropilaelaps mites as well as the current spread of the Yellow Legged Hornet (commonly referred to as the Asian Hornet), are you broadly optimistic for the future of Honey Bees in Britain?

It seems likely that the Asian Hornet (Vespa velutina) might finally have a toehold in the UK and we could have a small breeding population. Until now, APHA (Animal and Plant Health Agency) and the National Bee Unit have done a great job tracing nests and destroying them, but if the population increases exponentially, it will be impossible to control – as has been the case in France and other places.

It is hard to say exactly how the arrival of the Asian Hornet will affect British beekeeping although, as with the arrival of Varroa Mites in the 1990s, I suspect there will be a steep decline in the number of people keeping bees. Chris Packham recently said that having Asian hornets might only mean the loss of a few teaspoonfuls of honey, but I strongly disagree with this sentiment. One nest of Asian hornets can consume 11.5 kg of insects in a season – that’s hundreds of thousands of insects. Perhaps people don’t mind if those insects are honey bees, but when the honey bees run out, other bees, wasps, flies, butterflies and so-on could become the target prey. Imagine how that might affect birds and other animals that rely on those insects – not to mention the crops that they pollinate. And bear in mind that one Asian hornet nest can produce 300 queens resulting in hundreds of new nests the following year.

Tropelaelaps, and particularly Small Hive Beetle, are two other potentially very problematic invasive pests. They haven’t been found here yet and there are import controls and a system of sentinel apiaries to try to prevent or detect their arrival. There are contingency plans to prevent their spread should they arrive but there are a lot of unknown factors. Climate change makes the possible arrival and spread of these exotic species more concerning.

I’m broadly optimistic about the future of beekeeping in the UK but there will be challenges and changes.

Finally, although I’m sure your job as editor of BeeCraft magazine, as well as your public speaking engagements must keep you incredibly busy (alongside the actual beekeeping of course!), we’d love to know if you have plans for further books?

I have lots of ideas for other bee-related books, some practical and some a bit more esoteric. Whether I’ll ever find time to write them, and in particular take the photographs for them, is another matter. At the moment, I’m glad to have finished this book and I am enjoying watching bees and visiting gardens without feeling the need to make notes and take photos – although my camera is never very far away…

Beekeeping for Gardeners is available from our online bookstore.

Beekeeping for Gardeners is available from our online bookstore.