In Hedges, Robert Wolton brings together decades of research and personal experiences from his farm in Devon to explore the ecology, biology, nature conservation and wider environmental values of the hedges in the British Isles. Containing over 300 photographs and figures, this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection offers a detailed commentary on hedges and their importance in our landscape.

In Hedges, Robert Wolton brings together decades of research and personal experiences from his farm in Devon to explore the ecology, biology, nature conservation and wider environmental values of the hedges in the British Isles. Containing over 300 photographs and figures, this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection offers a detailed commentary on hedges and their importance in our landscape.

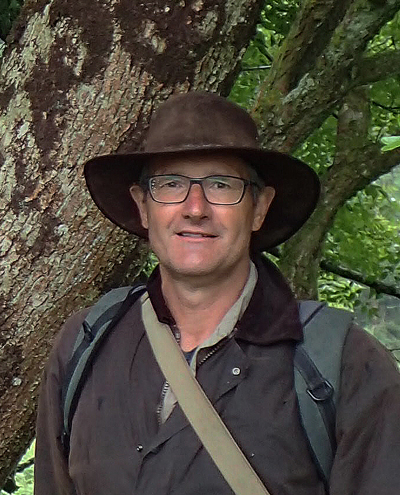

Robert is an ecological consultant and writer specialising in the management of farmland and associated habitats for wildlife. He is a former hedgerow specialist for Natural England, the founder, chair, editor and lead author of the Devon Hedge Group, has been involved in Hedgelink since it began, and has written a number of reports and articles specialising in hedges.

Robert is an ecological consultant and writer specialising in the management of farmland and associated habitats for wildlife. He is a former hedgerow specialist for Natural England, the founder, chair, editor and lead author of the Devon Hedge Group, has been involved in Hedgelink since it began, and has written a number of reports and articles specialising in hedges.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to be contributing to the British Wildlife Collection with a book on hedges?

I’ve had a life-long interest in natural history, even as a schoolboy I was a very keen birdwatcher. Later, at university, I trained as a zoologist with a strong interest in mammals, although subsequently I have been more involved with insects, especially moths and flies. It was perhaps inevitable that I should pursue a career in nature conservation. My passion for hedges was awakened when we bought a small farm in the heart of Devon, my wife, Paula, looking after the cattle and sheep while I went to the office. Initially it was the flower-filled meadows that drew me to the land, but I soon realised that the many thick hedges, full of different trees and shrubs, were glorious and just as special, particularly when I discovered that those small spherical nests I kept finding were made by Hazel Dormice. At that time, 30 years ago, hedges were very under-appreciated in the nature conservation world – there was a gap waiting to be filled and I was able to persuade my bosses in English Nature to allow me to become a part-time national hedge specialist, a role I continued to fill after the organisation morphed into Natural England. Partial retirement gave me the opportunity to write a book on my beloved hedges. I’d always dreamt of having a volume in the British Wildlife Collection, much admiring the series, so when Bloomsbury offered me the chance I jumped at it.

I tend to think of hedges as being man-made. But is there such a thing as a natural hedge? And if so, how do these come about?

Most hedges in Britain and Ireland are indeed man-made. Some, though, have grown up naturally along fence lines and ditches – these are termed spontaneous hedges and I think they are becoming more frequent, especially along the sides of roads and railway lines. Trees and shrubs, their seeds carried by wind, birds and mammals, can colonise strips of rough grassland remarkably quickly, often protected to begin with by brambles. It does not take many years before there’s at least a proto-hedge present, and after a decade or two it may be difficult to tell it was not planted. Another way hedges have come into being is through strips of woodland being left when land is cleared for agriculture. These are called ghost hedges. Their origin is often given away by the presence of unexpectedly high numbers of trees and herbs characteristic of ancient woodland because they have poor dispersal abilities.

I particularly enjoyed the chapter in your book on the origins and history of hedges. Do you think that the study of hedges can give us an insight into the natural and social history of our country?

Without a doubt. Throughout our countryside, away from the open moors and fens, the pattern of fields, as defined by hedges and sometimes drystone walls, allows the history of the landscape to be read, often going back centuries, even sometimes millennia. We are so fortunate in these islands still to have this landscape continuity – it has been lost over much of continental Europe. In places like Dartmoor, which I can see from our farm, layer upon layer of history can be unpicked through studying the networks of field boundaries, most of which are banked hedges. Some can be traced back to the Bronze Age, 3,500 years ago. This may be exceptional, but even so, most of the hedges in Britain, and many in Ireland, probably date back to Medieval times. They are a hugely important part of our cultural heritage. We love our hedges. This is evident not just in the countryside, but across our villages, towns and cities, in our gardens and parks. Hedge topiary is, after all, a national pastime!

As you describe early on in the book, there are many different types of hedge, from those that consist of just a single species to very diverse multi-species ones, even ones that have been allowed to mature into lines of trees. Is there a type of hedge that is best for the surrounding wildlife and environment and that we should be trying to replicate or maintain as much as possible?

If you put me on the spot, I’ll answer this question by saying that thick, dense, bushy hedges are the best for wildlife, preferably with margins full of tussocky grasses and wildflowers. But really we should be thinking about what networks of hedges look like, because there’s no such thing as a perfect hedge. Different birds, mammals and insects like different conditions, and in any case you can’t keep a hedge in the same state for ever, however carefully you manage it. Basically, the trees and shrubs are always trying to reach maturity, and as they do so gaps develops beneath their canopies and between them. That’s when laying or coppicing are needed, to rejuvenate the hedge and make it more dense and bushy. A lot more research needs to be done on this, but probably, from a wildlife point of view, at least half of all the hedges in a network, say that covering a decent-sized farm, should be in this condition. On the other hand, from a climate perspective, where we need to capture as much carbon as quickly as possible, tall hedges with many mature trees are best. You can see there are tensions here, all part of the challenge of managing hedges well. Who said it was easy?

As both a farmer and an ecologist, I’m sure you are more attuned than many to the conflicting needs of making a living from the land and managing hedges for the benefit of wildlife and conservation. Do you think financial incentives are the only way to encourage landowners and farmers to both plant more and maintain existing hedges?

Financial incentives like government grants will always be important to landowners and farmers because good hedges benefit society at large just as much as those who own and manage them. Things like plentiful wildlife, carbon capture, reduced risk of homes flooding and beautiful landscapes rarely bring in any income to offset costs, let alone profit – it is right that they are supported from the public purse.

Still, hedges can be of direct financial value to farmers through serving as living fences, preventing the loss of soil or providing logs and wood chips for heating. They can also increase crop yields through boosting numbers of pollinators and the predators of pests. To some extent, these direct benefits to farm businesses have been forgotten in recent decades in the drive for increased food production regardless of environmental cost, but they are now being appreciated much more as new ways of working the land, such as regenerative farming, catch on.

And we should not overlook the fact that more and more landowners and farmers are prepared to bear at least some of the costs of good hedge management simply because they gain huge satisfaction from healthy hedges and all the wildlife they contain. The pleasure of seeing a covey of Partridges or a charm of Goldfinches, or hearing the purring song of the Turtle Dove, cannot be priced.

Finally, how did you find the experience of writing this book, and will there be other publications from you on the horizon?

This is my first ‘big’ book, and I was apprehensive to say the least when I started writing it, in 2022. But with a lot of encouragement from my wife and friends I soon got into the swing of things. Challenging for sure but personally most rewarding – exploring new facets, checking information and trying to find the best way to pass on my enthusiasm for the subject. Above all, it felt good to share knowledge collected over many years. Bloomsbury’s support was invaluable, there’s no way I could have self-published. As to whether there are more books in me, I’m not sure. Perhaps one on hedges in gardens? There again, I have a passion for wet woodland, another habitat that’s been much neglected. It’s all too soon to say.

Hedges is available to order from our bookstore.

Hedges is available to order from our bookstore.