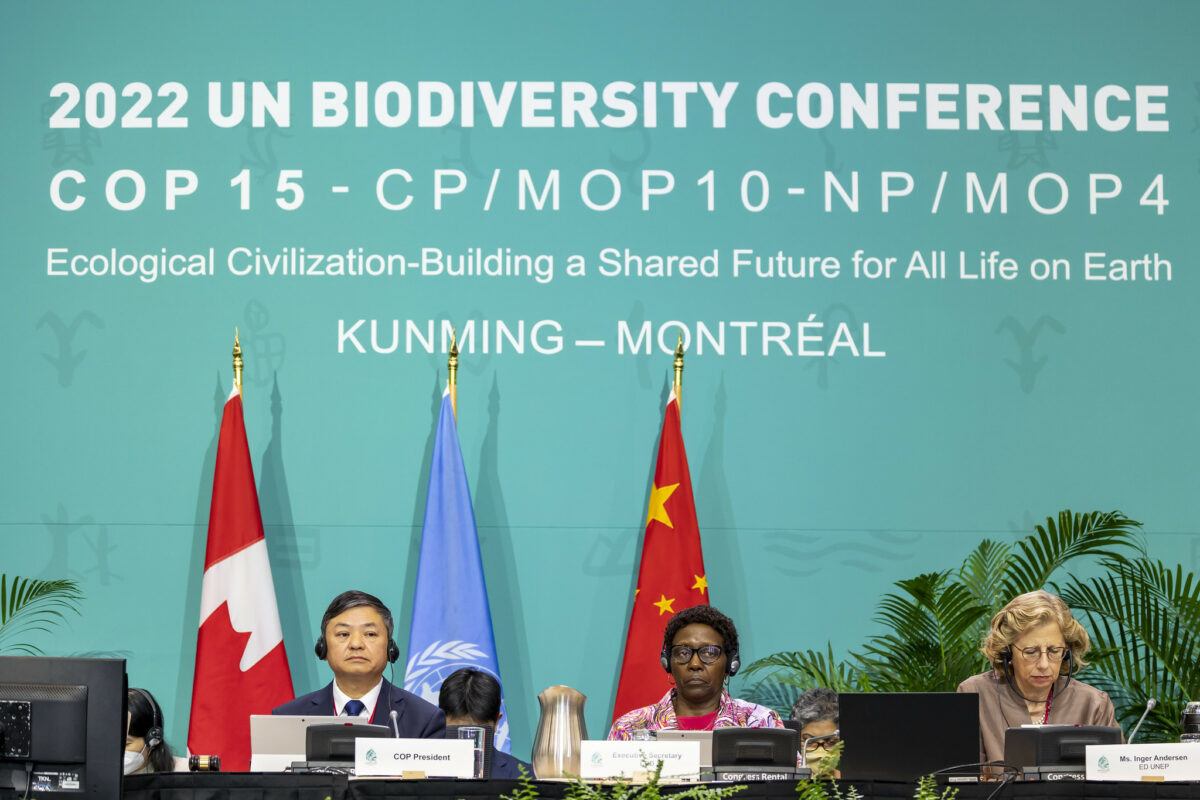

COP15, the UN Biodiversity Conference, took place between 7th and 19th December 2022. This event set out to convene world governments to agree to a new set of goals for nature over the next decade. This will create a framework that sets out an ambitious plan to implement broad-based action to change society’s relationship with biodiversity, ensuring that humanity can live in harmony with nature by 2050. COP15 has been touted as the key turning point in the fight to protect biodiversity, and a vital opportunity for countries to make change.

Biodiversity is declining globally, with the WWF Living Planet Report reporting that trends in the population abundance of mammals, fish, reptiles, birds and amphibians have revealed that populations have declined by an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018. Habitat conversion for people and livestock, hunting, exploitation, the intensification of agricultural practices, and the impacts of climate change such as temperature increase, changes to rainfall patterns and increased extreme weather events are among the wide range of challenges wildlife currently faces. Regionally, Latin America and The Caribbean have experienced the worst decline, at 94%. This global decline is set to worsen if no changes are made.

What were the goals that needed to be set?

The main aim of COP15 was to reach a set of goals and targets that would create a comprehensive and equitable framework agreed upon by world governments. These clear targets need to address over-exploitation, pollution, fragmentation and unsustainable agricultural practices, and be matched by the resources needed for implementation. There also needed to be a plan that safeguarded the rights of indigenous peoples, recognising their contributions as stewards of nature. Finally, the finance for biodiversity needed to be addressed, particularly relating to the alignment of financial flows with nature to push finances towards sustainable investments and away from environmentally harmful ones.

The Deal

An agreement was reached on Monday 19th December 2022. Almost 200 countries agreed to the new set of goals and targets that aim to “halt and reverse” biodiversity loss by the end of the decade. Six items were adopted at COP15:

- the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

- A monitoring framework for the Kunming-Montreal GBF

- Mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review

- Capacity-building, development, technical and scientific cooperation

- Resource mobilisation

- Digital sequence information on genetic resources.

It is hoped that measurable targets within the Kunming-Montreal GBF, and a mechanism for implementation, will ensure it will succeed where previous targets have not. There are 23 global targets within this GBF for 2030, with 10 ‘milestones’, including ensuring that at least 30% of land and water considered important for biodiversity are protected before the end of the decade. Currently, only 17% of terrestrial and 10% of marine areas are protected.

The key targets also include increasing financial resources from all sources, not just governments, to at least $200 billion per year towards supporting biodiversity by 2030; reducing, redirecting or reforming environmentally harmful incentives by $500 billion per year; and reducing the nutrients lost to the environment by at least 50%, pesticides by at least two thirds and eliminating plastic waste from entering the environment entirely.

The digital sequence information target refers to genetic sequence data, derived from the natural world. This is used in medicine and science, for vaccines, biofuels, crop improvements and further research. The target would require that the benefits arising from this information be shared fairly and equitably.

Are they effective?

Many are labelling the goal of taking urgent measures by 2030 as a strong call to action, with many 2030 milestones listed in the final agreement, including reducing extinction risk by 20%. This would then be reduced tenfold by 2050. This, however, would mean many species are still likely to go extinct during this time, particularly specialist species that occupy narrow niches, as these are more likely to be impacted than generalist species that can survive in a wider variety of environmental conditions. Reducing the diversity of species within an ecosystem can reduce its resilience against other stressors, such as the impacts of climate change, disease and habitat degradation. This is known as biotic homogenisation, where ecological communities become increasingly similar due to a combination of the extinction of native species and the invasion of non-native species.

The target of protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030 is hailed by many as the main success of the conference. This large increase in protected areas, especially with the requested focus on areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, will have a significant impact on  biodiversity loss. However, some are describing the milestone of conserving at least 30% of land and sea by 2030 as a ‘floor, not a ceiling’, suggesting that 50% is an important step to the long-term survival of both biodiversity and humanity. This is the key aspect of the Half-Earth concept, developed by biologist E. O. Wilson, which states that the only solution to the upcoming ‘Sixth Extinction’ is to increase natural reserves to cover half the surface of the earth.

biodiversity loss. However, some are describing the milestone of conserving at least 30% of land and sea by 2030 as a ‘floor, not a ceiling’, suggesting that 50% is an important step to the long-term survival of both biodiversity and humanity. This is the key aspect of the Half-Earth concept, developed by biologist E. O. Wilson, which states that the only solution to the upcoming ‘Sixth Extinction’ is to increase natural reserves to cover half the surface of the earth.

Additionally, there is no target for increasing species population abundance by 2030, with details on enlarging the area of natural ecosystems by at least 5% being removed after earlier drafts. While many of the other targets will most likely lead to an increase in species population abundance, and perhaps even in increasing the area of natural ecosystems, the lack of a set target makes it harder to hold governments to account.

Another item that has notably been missed is the issue of dietary consumption, beyond reducing general overconsumption. Research has shown the consumption of meat, particularly beef, is specifically linked to biodiversity loss, with 30% of biodiversity loss linked to livestock production. Reduction of meat consumption is not mentioned in the text of the COP15 agreement, despite research suggesting that beef consumption needs to fall by 90% in western countries to prevent the future impacts of climate change.

Research has also shown that over £1.48tn ($1.8tn) of environmentally harmful subsidies are being paid each year, going towards high-emission cattle production, deforestation and pollution. One of the Aichi biodiversity targets, discussed later in this article, was to remove these subsidies, which governments failed to achieve by 2020. This new target, which requires governments to redirect or reduce these subsidies by at least £416bn ($500bn) per year is a major opportunity, and is recognised as another major outcome of this agreement. However, this still leaves over £1tn ($1.3tn) in environmentally harmful subsidies each year, continuing to put pressure on global biodiversity.

Additonally, the COP15 agreement calls for businesses to assess and disclose how they impact and are impacted by nature loss, but it is not mandatory, which weakens this target. This is unlikely to effectively hold large corporations to account, though societal pressure may play a role in encouraging many countries and financial firms towards disclosures.

This all suggests that, while meeting these targets will put the world on the right track towards halting and reversing biodiversity loss, there is still much more that is needed to be done to create a ‘nature-positive’, more harmonious future. These targets need to be a starting point rather than an end goal.

Can we rely on these promises?

The previous strategic plan for biodiversity for the 2011-2020 period included the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, agreed upon at COP10 in 2010. However, by 2020, the Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 Report by the UN showed that the world failed to meet any of the targets. There were 20 targets agreed upon, which were separated into 6o elements, to aid in monitoring overall progress. In 2020, only seven of these elements were achieved, with 38 showing progress and 13 with no progress at all. Two had unknown progress. This resulted in six Aichi targets being partially achieved, such as those on protected areas and invasive species. This failure to meet the previous set of targets does not bode well for any confidence in the seriousness of the commitment of world governments to meet these new ones.

The new financial targets, widely hailed as one of the main successes of COP15 will make a huge difference in halting and reversing biodiversity loss but only if they are actually achieved. In 2009, developed countries committed to supplying $100 billion per year by 2020 to help vulnerable countries impacted by climate change. However, these rich nations failed to meet the long-standing pledge. Instead, $83.3 billion was provided in 2020, $16.7 billion short of the target. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggested that the $100 billion target would not be met until 2023, using U.N. data processed with a two-year delay. This, again, casts doubt on whether developed countries can be relied upon to follow through with the financial commitments agreed upon at these events.

The other main success of COP15, the goal to protect 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030, also has a failing precedent. In the UK in 2020, the Prime Minister at the time, Boris Johnson, committed to protecting 30% of the UK’s land and sea for nature by 2030. However, so far, according to the 2022 Progress Report on 30×30 in England by Wildlife and Countryside Link, only 3.22% of England’s land is effectively protected and managed by nature, compared to 3% in 2021. There was more progress in protecting English waters, with 8% effectively protected for nature, compared to 4% in 2021. With very little progress being made and the continued threats of deregulatory proposals to reform or repeal the strongest laws for nature, this calls into question whether the UK will remain committed to these new global goals. Additionally, the newly published environmental targets from The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) are being criticised as a ‘job half-done’ as the goals to ensure greater biodiversity in 2042 than in 2022, and at least 10% more than in 2030, do not go far enough.

However, a proposed EU Nature Restoration Law might be the first step towards achieving these new targets. Should this law successfully make its way through the European Parliament, it would signal that these countries are willing to make the necessary policy changes to stop biodiversity loss. The new law aims to set specific timetables for restoring degraded habitats such as rivers, wetlands, fields and forests. It would cover 1.6 million square miles across the 27 member countries. As the EU’s current environmental laws don’t explicitly state how, when or who needs to restore these areas, this new law is a much-needed addition to ensure proper implementation of conservation. The final vote is expected to take place in June.

Ultimately, world governments and global businesses have made similar pledges before and failed to follow through. Often, while the agreements contain targets that would make significant progress against biodiversity loss, there is a lack of strict regulation of adherence and adoption of policies that would allow for progress towards these targets. While there have been some initial steps that suggest a real commitment to achieving these targets, the next few months and years will be a key time for world governments to prove that they are willing to make the necessary changes.

References and useful resources

The UN page on COP15

The first draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework

The 23 targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

Two papers on the impacts of biotic homogenisation

Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life by Edward O. Wilson

Research into meat consumption and its connection to biodiversity loss

Research into food systems and environmental limits, discussing the reduction of meat consumption

Research into the amount of environmentally harmful subsidies per year

The Aichi Biodiversity Targets

The world failed to meet any of the Aichi biodiversity targets by 2020 – a news report by The Guardian

The statement by Defra on the final environmental targets under the Environment Act 2021