Earth to Earth: A Natural History of Churchyards, an interview with Stefan Buczacki

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written a passionate call-to-arms for the future conservation of this important and vital habitat.

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written a passionate call-to-arms for the future conservation of this important and vital habitat.

Stefan has answered a few questions regarding the natural history of churchyards and what we can do to conserve them.

You refer to a Modern Canon Law, derived from an older law of 1603 that all churchyards should be ‘duly fenced.’ How important was that law in creating the churchyards we’ve inherited?

Hugely important because although some churchyards had been enclosed from earlier times, the Canon Law making it essential was what kept churchyards isolated/insulated from changes in the surrounding countryside.

I was fascinated by the ‘ancient countryside’ lying to the east and west of a broad swathe from The Humber, then south to The Wash and on to The New Forest: could you expand on that division you describe?

The division into Planned and Ancient Countryside has been known and written about since at least the sixteenth century but the geographical limits I mentioned really date from the area where the Enclosure Acts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were so important. The more formal Planned Countryside landscape has been described as having been ‘laid out hurriedly in a drawing office at the enclosure of each parish’ whereas the fields of Ancient Countryside have ‘the irregularity resulting from centuries of ‘do it yourself’ enclosure and piecemeal alteration’.

If cemeteries, particularly enclosed cemeteries offer a ‘time capsule’ are there any current development or initiatives you can think of that future generations will consider as a similar natural heritage?

A difficult one but I suppose the closest might be SSSIs and comparable wild life reserves. National Parks might be thought candidates, but they are too large and too closely managed.

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

Only by gentle education and by informed churchyard support groups giving guidance and instruction to the wider community. The other side of the coin to that you describe – and equally damaging – is where a churchyard support group itself believes that by creating a neat and tidy herbaceous border in their churchyard to attract butterflies they are doing something worthwhile! A little learning is a dangerous thing.

A whole chapter is devoted to the yew tree; such a familiar sight in so many churchyards. There are many theories as to why yews were so often planted within churchyards. From all the theories in your book, which one do you think has the most credence?

That Christianity inherited and then mimicked pre-Christian/Pagan activity without knowing – as we still do not – what its original significance might have been. There is so little documentary evidence from pre-Christian times.

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status?

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status?

Without question lichens; because there are just so many species largely or even wholly dependant on the churchyard environment – the gravestones and church buildings.

With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard?

With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard?

Without doubt, the first step should be to conduct a survey of what is there already; and be aware this is not a task for well-intentioned parishioners unless they have some specialist knowledge. The County Wildlife Trusts would be my first port of call as they will have all the necessary specialist contacts. Then it will be a matter – with the specialist guidance – of developing a conservation management plan.

If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

- Discuss the project with your vicar/priest/diocese to explain your goals and obtain their support. Show them my book!

- By whatever means are available [parish magazine, website, email…] contact the parish community at large to explain that you hope [do not be too dogmatic or prescriptive at this stage] to take the churchyard ‘in hand’ and ask for volunteers – but do not allow well-meaning mavericks to launch out on their own. And continue to keep people informed.

- See my answer to Question 7 – and undertake a survey.

- As some people will be keen to do something positive straightaway, use manual/physical [not chemical methods] to set about removing ivy that is enveloping gravestones and any but very large trees. It should be left on boundary walls and to some degree on large old trees – provided it has not completely taken over the crown – but nowhere else.

- Use a rotary mower set fairly high to cut the grass; again until the management plan is developed.

- Set up properly constructed compost bins for all organic debris – and I mean bins, not piles of rubbish.

- Do not plant anything either native or alien unless under proper guidance – least of all do not scatter packets of wild flower seed. You could be introducing genetic contamination of fragile ancient populations.

- Stop using any chemicals – fertiliser or pesticide – in the churchyard; at least until the management plan has been developed.

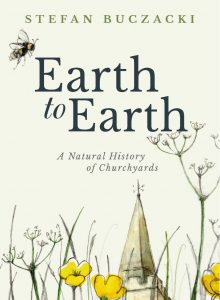

Stefan’s book Earth to Earth: A Natural History of Churchyards was published in March 2018 is currently available on special offer at NHBS.

Earth to Earth: A Natural History of Churchyards

Hardback | March 2018

£12.99 £14.99

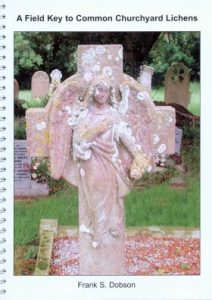

Further reading on lichen in churchyards…

A Field Key to Common Churchyard Lichens

Spiralbound | Jan 2014

£9.99

Guide to Common Churchyard Lichens

Unbound | Dec 2004

£2.99

Please note: All prices stated in this article are correct at the time of posting and are subject to change at any time.

Thank you so much, MarK!