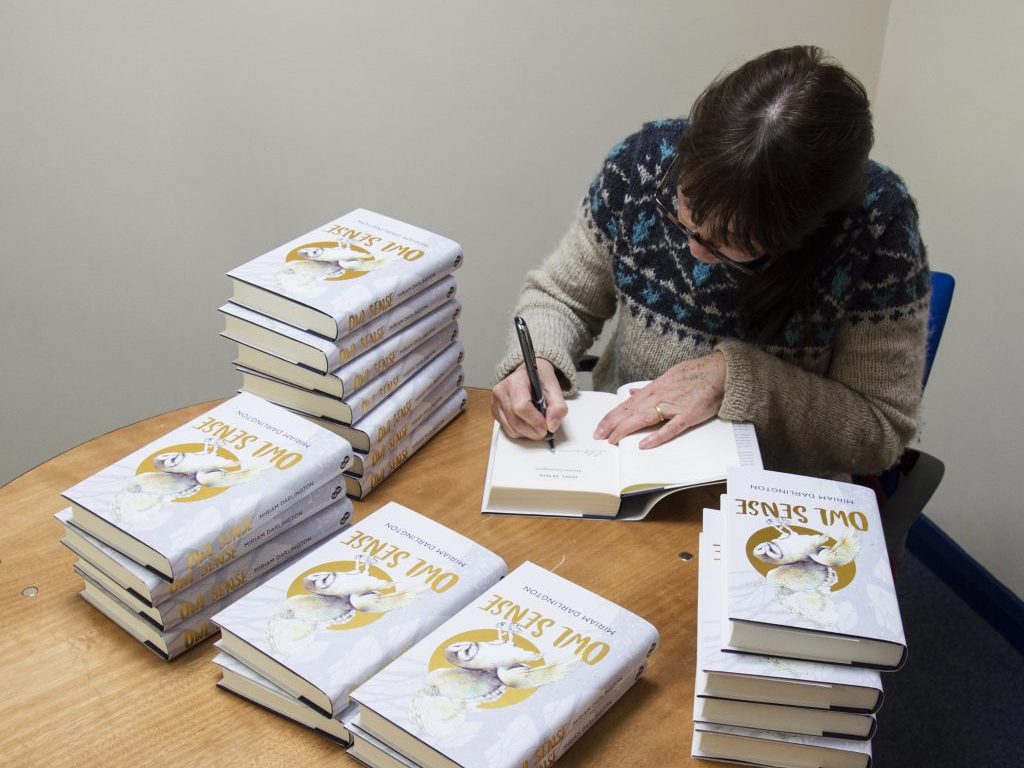

We currently have a limited number of signed copies available!

For most of her life, Miriam Darlington has obsessively tracked and studied wildlife. Qualified in modern languages, nature writing and field ecology, she is a Nature Notebook columnist at The Times. Her first book, Otter Country was published in 2012 and her latest book, Owl Sense was recently Book Of Week on BBC Radio 4.

We recently chatted to Miriam concerning her quest for wild encounters with UK and European owls.

It seems the main threat to barn owl numbers is the way our landscape has changed regarding commercial development and farming methods. What do you think is the single most important action regarding land management that could halt their decline and get their numbers growing sustainably?

It is all about protecting the owls’ habitat. As field vole and small mammal specialists the owls need rough grassland, where the small mammals live. The rough grassland needs to be protected, and wide enough strips around the field margins maintained and left so that a deep, soft litter layer of dead grasses can build up. This litter layer is essential for voles to tunnel through; this is what they need to survive, so it is all about helping farmers to be aware of this and funding them to manage this type of wildlife-friendly grasslands. Nesting sites are also vital; as mature trees are not replaced, and barns are unsympathetically converted, the owls will have no roosts and no nesting sites. Barn Owls need specialised, sheltered nest boxes in farm buildings. If they can feed, they can breed, and if they can breed they will continue to grace our countryside.

The volunteer work you undertook with The Barn Owl Trust was very interesting, but seemed quite intrusive to these reclusive, easily alarmed birds. What can you say to assuage my concerns?

The volunteer work you undertook with The Barn Owl Trust was very interesting, but seemed quite intrusive to these reclusive, easily alarmed birds. What can you say to assuage my concerns?

The Barn Owl site surveys that I observed and described may seem like an intrusion, but it was a vital part of the BOT’s conservation work and always carried out with the utmost care. I would describe it as a necessary intrusion, as it was part of a 10-yearly survey, an information gathering exercise altogether essential for our knowledge of how many owls are breeding in Devon and the South West. The status and numbers of occupied sites were ascertained, and farmers, landowners and general public could be advised accordingly; nest boxes were repaired or replaced, risks assessed and owners given invaluable conservation advice. I described an incident in the book where an owl flew out of the barn we were surveying, demonstrating that owls are very sensitive, the utmost care is always taken, and the laws around the protection of owls are very strict. We were working in warm, dry conditions and no harm came to the owls. The Barn Owl Trust work under licence from Natural England, knowing that if any owl is inadvertently disturbed, they will usually quickly return to their roost. However, with the risks in mind, the greatest care and respect as well as a strict protocol was always followed when surveying sites . We had to work quietly and quickly, counting, ringing and weighing young as rapidly as possible with no time wasted. Adult owls often roost away from the nest due to it being full of pestering young, so they were usually unaffected by our visit. In other cases, the adult owl(s) looked but stayed put as they were well hidden. In some cases, for instance busy working farm barns, the owls are used to all sorts of noise, machinery and disruption, and were completely habituated, and not disturbed at all. Most of the time the adult owls I saw were vigilant, rather than stressed. The young have no idea what is happening and become biddable when approached. All-in-all, the value of the data we gathered would far outweigh any small intrusions. But the general public should be aware that it is illegal to recklessly enter a nesting site without a licence, especially with the knowledge that owls are breeding there.

Historically, owls were viewed as harbingers of doom. This seems to have been replaced by the commercial ‘cutifying’ of owls. Can this still be considered a sort-of reverence – is this the best regard wild animals can now expect?

Historically, owls were viewed as harbingers of doom. This seems to have been replaced by the commercial ‘cutifying’ of owls. Can this still be considered a sort-of reverence – is this the best regard wild animals can now expect?

No, I feel we need more than that; we need to respect their wildness, not their cuteness. Humans need to remember to keep our distance; the owls are not there for our enjoyment after all, but as a vital part of a healthy ecosystem. It helps to attract our attention that they are beautiful and charismatic, and it can be thrilling to catch sight of one, but I don’t feel that simply seeing them as cute is any help at all. We need a deeper respect for them than that. We need to care for, respect and understand their needs, but I think reverence is probably too much to ask! I would say sympathy is important, and that should be taught/encouraged in schools.

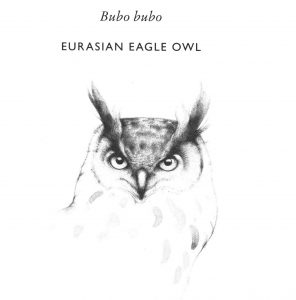

I found the descriptions of Eagle Owls foraging around waste dumps quite disconcerting. Away from their natural environment, sustaining themselves on human waste seems a sad fate for any animal, let alone a magnificent eagle owl. Am I being overly sentimental and unrealistic?

I found the descriptions of Eagle Owls foraging around waste dumps quite disconcerting. Away from their natural environment, sustaining themselves on human waste seems a sad fate for any animal, let alone a magnificent eagle owl. Am I being overly sentimental and unrealistic?

Yes, it’s easy to see only ugliness there, and it seems like a shame, yes perhaps it is disconcerting, but it shows these creatures are adaptable. It is not desperation, it is opportunistic…and they were feeding on rats, not human waste, so it was probably win-win.

Staying with human and wild animal interactions, you mention recent new builds and the impact they can have. As the rate of new builds is unlikely to decline, do you think developers could do more to take wildlife into account and, if so, what would these measures look like and how would they be enforced?

Staying with human and wild animal interactions, you mention recent new builds and the impact they can have. As the rate of new builds is unlikely to decline, do you think developers could do more to take wildlife into account and, if so, what would these measures look like and how would they be enforced?

I believe developers are legally obliged now, and have been for some years, by local authorities, to survey for wildlife and to mitigate for any wildlife found to be breeding there. I visited a site on the edge of my town recently where some of the houses had bat boxes and swift boxes. It is legally enforced already, but many people may be unaware of this.

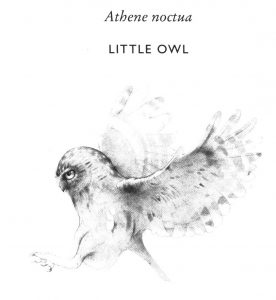

Captive owls are increasingly popular, and you wrote a reflective passage concerning a little owl called Murray. Even naming a wild animal is anathema to many conservationists. However, your initial concern about a captive owl seemed to diminish as you saw the effect it had on the audience. Do you think displaying captive birds can help conservation efforts?

Captive owls are increasingly popular, and you wrote a reflective passage concerning a little owl called Murray. Even naming a wild animal is anathema to many conservationists. However, your initial concern about a captive owl seemed to diminish as you saw the effect it had on the audience. Do you think displaying captive birds can help conservation efforts?

It is very complex. I don’t think keeping and displaying captive wild animals is the best idea, ultimately. Humans have been domesticating animals for millennia however and it is interesting to look at the long view. Although I am very uncomfortable with keeping wild animals as pets, I have witnessed two things: 1. That when they are kept properly by experienced professionals, they do not seem to suffer and can lead long and relatively safe and healthy lives; and 2. that they can have benefits; increased sympathy and understanding for the species, aspirational opportunities for marginalised people, help for suffering or socially isolated people. I’m not a scientist however. I don’t feel qualified to make the final decision on this. It’s easy to pontificate about the morality of it all, and to see the risks, but not so easy to untangle the costs to the animal and the benefits, economic, emotional and otherwise to some humans. In the end, when we wanted an animal for my family, we got a domestic dog, not an owl. I think that’s the best one could wish for, in the circumstances.

In your previous book Otter Country you describe the places you are in with as much awe as the animal you are hoping to see – the same with Owl Sense. Is it the wild place or its occupiers that move us? Even the government’s recent 25 Year Environment Plan alludes to the mental and physical health benefits natural spaces can provide; do you think conservation efforts would be better focused on wild places for their own sake or concentrate on the fauna and flora that inhabits them?

In your previous book Otter Country you describe the places you are in with as much awe as the animal you are hoping to see – the same with Owl Sense. Is it the wild place or its occupiers that move us? Even the government’s recent 25 Year Environment Plan alludes to the mental and physical health benefits natural spaces can provide; do you think conservation efforts would be better focused on wild places for their own sake or concentrate on the fauna and flora that inhabits them?

You can’t separate the two. The habitat comes first, but any expert will tell you that the animals are inseparable from their natural habitats. Look at what happened when wolves were reintroduced to Yosemite. The whole ecosystem began to restore itself when the wolves came back. My philosophy is to describe both; I feel passionately about the connections of the whole ecosystem, including the humans in it. I want to engender understanding and sympathy for that inseparableness. For most people, however, I expect going to a countryside place or a wild place is the most important, and encountering a wild animal, or knowing that there is a possibility of it will come second. I have focussed on owls and employed them as ambassadors, and animals can certainly attract public sympathy, but I suspect it is ownership of the land, stewardship of the land, the economic, health and social impacts of the land, that might win us the argument.

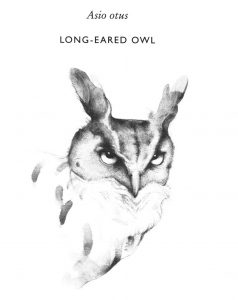

Your journey to Serbia to see the long-eared owls was amazing. So many owls, living in apparent harmony in close proximity to humans. As these spaces develop, however, this balance will of course shift, and not in favour of the owls. The only hope offered seemed to be tourism and, ironically, hunters preserving the landscape. Do you see these two options as the only solutions to ensuring the long-term survival of long-eared owls in Serbia?

Your journey to Serbia to see the long-eared owls was amazing. So many owls, living in apparent harmony in close proximity to humans. As these spaces develop, however, this balance will of course shift, and not in favour of the owls. The only hope offered seemed to be tourism and, ironically, hunters preserving the landscape. Do you see these two options as the only solutions to ensuring the long-term survival of long-eared owls in Serbia?

Yes. I wouldn’t call it harmony necessarily, more like tolerance! The owls have been coming to the towns for many, many years and that will not change as long as the roost trees are preserved and farming does not intensify too quickly. As with Barn Owls, the owls need to fly out into the fields as they feed on the small rodents and small birds in the farmland.. this may become threatened with changes in farming as the country becomes more prosperous. Ecotourism will probably protect the state of things, as with the large owl roosts that are so spectacular; this economically deprived country needs every help it can get. The local people have caught on to this, but the authorities have some way to go with supporting it and fully and sustainably harnessing it. They key would be to harness ecotourism wholeheartedly. And yes, the hunters wish to preserve the habitats, which is excellent. It seems like the best arrangement, in the circumstances, and probably quite sustainable.

Your French guide, Gilles alluded to a dislike towards bird watchers (les ornithos) in the provinces. He said that, while in the countryside, he couldn’t leave his bird book on show in the car as people would slash his tyres. Things aren’t so bad here in the UK, but do you consider being a conservationist akin to being a radical and a subversive? – has protecting the environment fully entered the consciousness of the mainstream?

Your French guide, Gilles alluded to a dislike towards bird watchers (les ornithos) in the provinces. He said that, while in the countryside, he couldn’t leave his bird book on show in the car as people would slash his tyres. Things aren’t so bad here in the UK, but do you consider being a conservationist akin to being a radical and a subversive? – has protecting the environment fully entered the consciousness of the mainstream?

I think it has entered mainstream consciousness, and has some superb advocates now, but the activists should never let down their guard; we all need activists keeping an eye because right now we can never afford to be complacent – complacency is a very human trait and one that has brought us into this mess. We need to be constantly asking questions, constantly probing, curious and vigilant, and if that is a form of activism, I’m with the activists. It’s about questions and sometimes challenges, I think that’s what the best journalism, environmentalism, nature writing, scientists and conservationists do best.

You make it clear that the decision to leave the EU is not what you would have wished for. Aside from potentially losing a connection with mainland Europe, do you envisage any pro and cons for the UK environment regarding Brexit?

You make it clear that the decision to leave the EU is not what you would have wished for. Aside from potentially losing a connection with mainland Europe, do you envisage any pro and cons for the UK environment regarding Brexit?

I’m not enough of an expert to be able to answer that. I was mortified to find that Britain was going to separate itself from what appeared to be a friendly and well-meaning, beneficial alliance, especially in terms of conservation regulations, but am completely naïve about the economic and the conservation implications for the future – I think we just have to continue working to call our leaders to account, and never lose sight of our priorities.

Owl Sense

Hardback | February 2018

£12.99 £15.99

Otter Country

Paperback | May 2013

£7.99 £9.99

Miriam’s writing centres on the tension, overlaps and relationships between science, poetry, nature writing and the changing ecology of human-animal relations. On a personal note I thought Owl Sense fulfilled this challenging undertaking. The personal and evocative writing, all underpinned by the ecology, biology and historical significance of these amazing animals made this a joy to read.

Miriam called into NHBS to sign our stock; these will be available only while stocks last.

NHBS currently have price-offers on Owl Sense and Miriam’s previous book Otter Country.

Please note: Prices stated in this blogpost are correct as of 15th February 2018 and may be subject to change at any time.