Over the last 6 months, NHBS has had the opportunity to work alongside Devon’s Living Churchyard Project by donating a number of bat and bird boxes to be installed in a range of churches across Devon to support local wildlife. This initiative aims to manage churchyards while also encouraging wildlife, biodiversity and promoting sustainable management practices.

We recently spoke with David Curry, former Voluntary Environmental Advisor at the Living Churchyard Project, about his role, the importance of preserving these habitats and more.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you first became interested in biodiversity, particularly within churchyards?

I began my career working as Keeper of Natural History at Plymouth Museum and Art Gallery, and later St. Albans museums in Hertfordshire. I am now retired, having worked mainly in local government for 50 years, where I first worked in heritage departments and planning.

My main role in planning was as an enabler – working with community groups in developing and managing wildlife sites – these ranged from changing derelict chalk stream cress beds into chalk wetlands, to planning and establishing community orchards ranging in size from 1ha to 72ha.

I’m an old-fashioned naturalist, today it’s called biodiversity.

In 1986 the Living Churchyard Project was set up by the Arthur Rank Centre to encourage the use of churchyards as a community environmental resource and to raise environmental awareness. I took an active interest in the project and began to visit and record churchyards in my area. I then lead the Devon Living Churchyards Project in a voluntary capacity for the Church of England’s Diocese of Exeter, while working in partnership with the national charity Caring for God’s Acre project.

What does the role of a voluntary Environmental Advisor entail?

September 2023 saw the publication of the 4th State of Nature (SON) Report.

The report provides the most comprehensive overview ever of species trends across the UK, laying bare the stark fact that nature is still seriously declining across a country that is already one of the most nature-depleted in the world.

The data shows that since 1970, UK species have declined by about 19% on average, and nearly 1 in 6 species (16.1%) are now threatened with extinction. This is a timely reminder, if we needed it, that the nature crisis isn’t restricted to far-off places like the Amazon or Great Barrier Reef – it is right here, on our doorstep. We are losing familiar wildlife that we cherish including the Hazel Dormouse and Skylark.

SON goes beyond the bare statistics to assess the evidence behind these differences, it also identifies the actions that are needed to recover nature. To quote the report; “We have never had a better understanding of the State of Nature and what is needed to fix it.”

Exeter Diocese

The Diocese of Exeter is part of the Church of England and covers the whole of Devon. There are over 600 churches in the diocese, many of them rural, and there are over 2,000ha of glebelands (areas of land owned by the Church of England) which are used as a source of income through rents etc.

Opportunities

So, what are the issues that that needed to be addressed? And what are the opportunities to address them?

Evidence from the State of Nature report, and elsewhere, points to four big on-the-ground changes that we can take to accelerate nature recovery:

- Improve the quality of our protected sites on land and at sea. These places have been chosen because they are special for nature, and wildlife should be thriving within them, yet too many are currently in poor condition.

- Create more, bigger and messier places for wildlife. Our wildlife needs more space, and we know that many species can benefit from habitats that are quick to create such as ponds, scrubby habitats and un-trimmed hedgerows.

- Reducing pollution on land (notably pesticides and excess fertilisers) and reducing the pressure on marine environments. This means more wildlife-friendly farming, forestry and fisheries.

- Targeted species recovery action. This can be very effective when applied to a high proportion of a species’ population, and is also key to bringing back lost species.

Churchyards and their unique habitats provide a recipe for recovery in that they can be used to create more, bigger and messier places for wildlife. But also, the local communities must have the chance to be part of these changes. Establishing a Nature Recovery Network of ‘honeypot’ churches has been key. A pilot scheme working with the South Devon National Landscapes Life on the Edge project and Buglife has surveyed churches along the South Devon B Line from Wembury near Plymouth to Brixham (2023/2024). From the data collected, we will be able to provide churchyard management action plans to improve the biodiversity of each site, creating ‘honeypot’ churches.

In Conclusion

The picture of ongoing nature loss painted by the SON report is stark. This isn’t just sad – nature loss undermines our economy, food systems and health and wellbeing. So, we owe it to nature, and ourselves, to make sure that it is the last State of Nature report to chart continuing decline. Churchyards, in particular the Living Churchyards project, can make a positive contribution towards nature recovery in Devon and ensure that the next SON report can document the start of nature bouncing back.

“Nature’s recovery in Devon is not something we can achieve alone. It needs the support of individuals, communities, businesses and schools.” Devon Wildlife Trust

Why do you think creating new habitats, and restoring old ones, is important for these spaces, and which species are you hoping to attract to the area with the installation of our habitat boxes?

Encouraging a diversity of species on a site is important. Installing the NHBS habitat boxes will provide both shelter and protection to various species such as bats, swifts, and bees.

Why do you think these vital areas of biodiversity are so often overlooked, and how do you think we can work to improve their future preservation?

Mention churchyards to anyone and they will usually shrug their shoulders.

A churchyard is many things to many people;

- A pleasant, reflective place for the congregation and visitors

- An environment in keeping with the function of burial and the scattering of cremated remains

- A respected and cared for part of our environment

No one mentions its potential as a sanctuary for wildlife. That’s the problem. People will walk past a church cemetery without giving a thought to looking inside, after all it’s a cemetery containing graves and memorials for the dead.

Raising awareness about the wildlife in the churchyard or the peace and tranquillity takes priority. We need to make the entrance more welcoming with appropriate signage.

‘People protect what they love’ – Jacque Yves Cousteau. This quote encapsulates the basic human instinct that drives us to safeguard and preserve the things that hold a special place in our hearts. Whether it be our loved ones, our communities or nature. At its core, this quote highlights the importance of connectiveness. Our modern culture has disconnected us from nature, and as ambassadors for nature we need to reconnect people, encourage people to understand and love nature and to be motivated to protect it.

Nature can also trigger positive emotions, reduce stress, increase prosocial behaviour, and improve health and wellness.

What are the most interesting species that you’ve found in some of the churchyards you’ve visit?

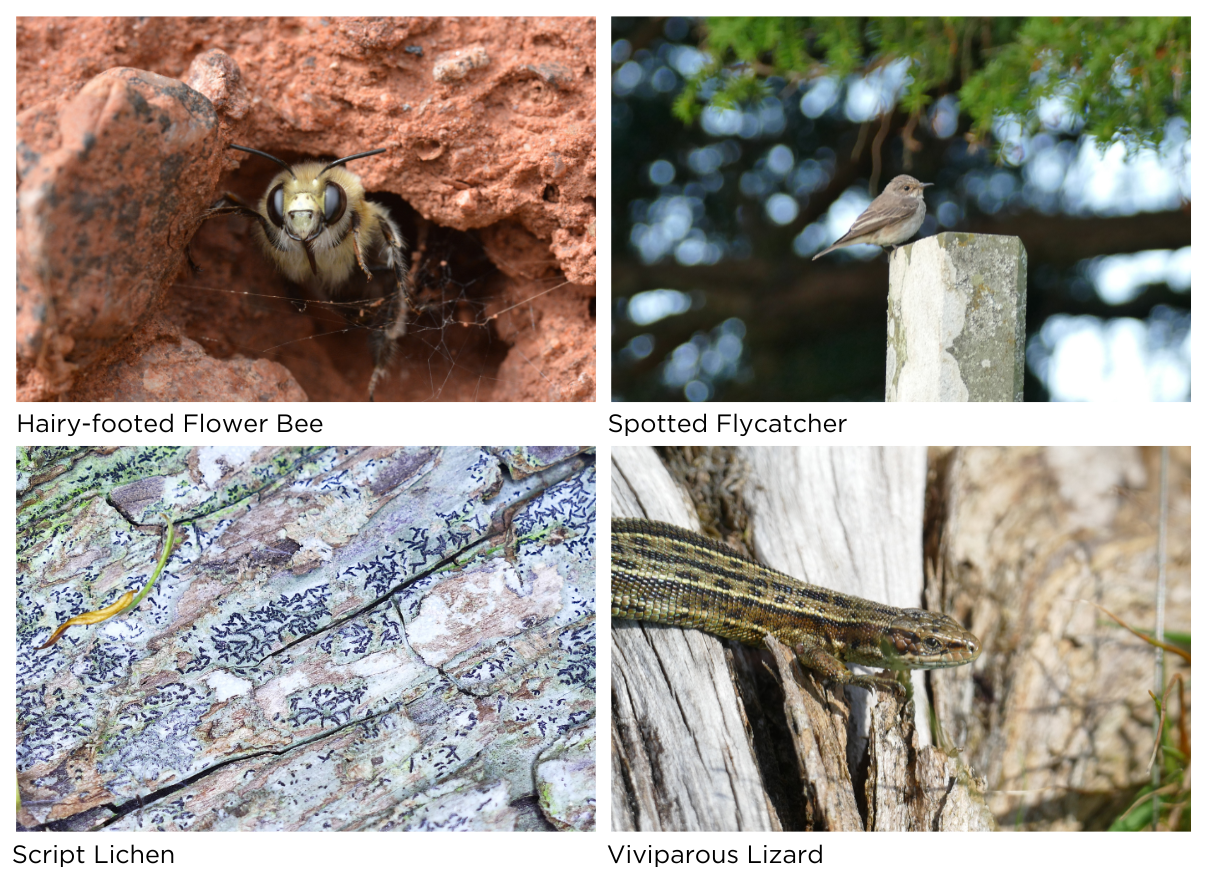

Gosh, how long is a piece of string? Because churchyards have been oases in space and time, largely immune from activities beyond their walls, they have become sanctuaries for a wide range of species. Churchyards provide a mosaic of habitats, from meadowland to woodland edge, dense hedges, short and long grass cover and a variety of ‘cliff’ and rock habitats in the form of the church wall and gravestones. They can harbour a startling number (often many hundreds) of species and no doubt conceal rare and interesting creatures and plants. The range of rock types on headstones are of special value to lichens and other lowly plants, some of which may be very rare.

Old cob boundary walls maybe especially interesting, offering hole nesting species including many species of solitary bees with places to lay eggs. These in turn attract the inevitable parasites, some of which are often over-looked but impressively sci-fi in appearance. Part of the peregrine falcon ‘come back’ after they dwindled to near extinction was fuelled by the nest site opportunities of church buildings – they are now a regular site perched on bell towers. Likewise, the shocking decline of swifts is now being reversed thanks to the installation of nest boxes in bell towers.

Love Your Burial Ground Week, celebrated every June, is an important opportunity to raise awareness of the importance of churchyards and celebrate their natural diversity. How can the local community get involved?

Saturday 7th June to Sunday the 15th June 2025.

Love Your Burial Ground Week is a celebratory week which has been running for many years. Caring for God’s Acre has been encouraging all who help to look after churchyards, chapel yards and cemeteries to celebrate these fantastic places in the lovely month of June – in any way you choose.

We’ve seen history talks, picnics, bat walks, storytelling, volunteering work parties and even abseiling teddy bears!

Churches Count on Nature 2025 runs at the same time as Love Your Burial Ground Week, and focuses on the brilliant wildlife to be found in churchyards and chapel yards. It is a joint initiative promoted by Caring for God’s Acre, the Church of England, the Church in Wales and A Rocha UK.

In the months leading up to June we shall be working with Caring for God’s Acre to encourage church communities throughout Devon to take part in this exciting event. There is a wealth of information on how you can open your churchyard to visitors provided by Caring for Gods Acre.