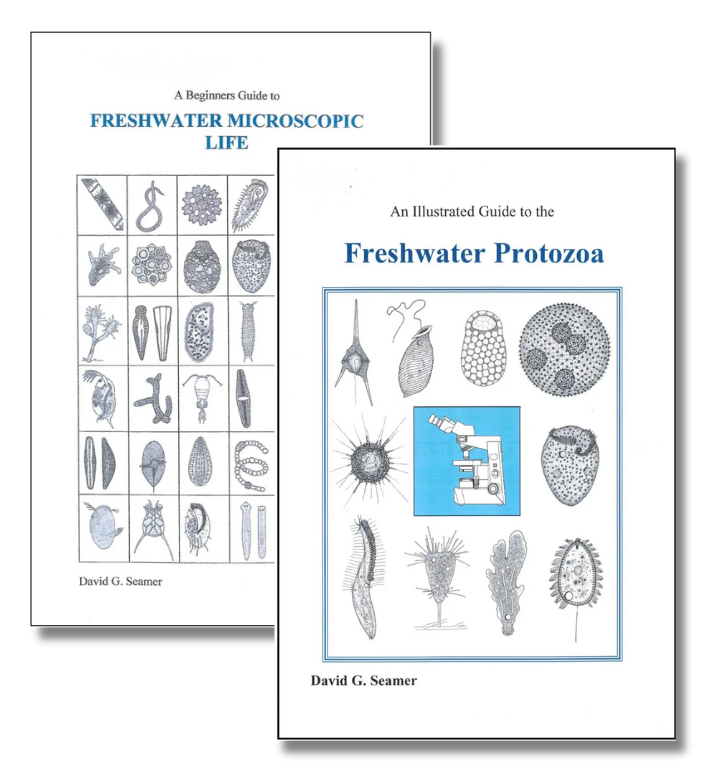

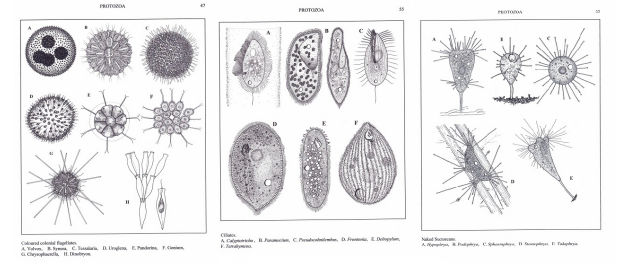

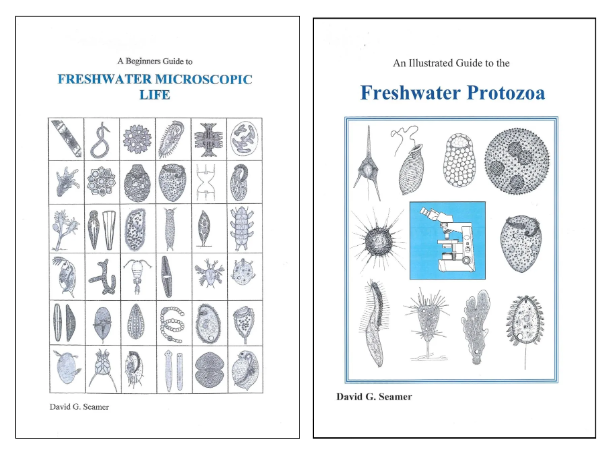

A Beginners Guide to Freshwater Microscopic Life is a practical, spiral-bound guide written by David Seamer which offers a fantastic introduction to the multitude of microscopic organisms found in freshwater. For those with a more specific interest, An Illustrated Guide to the Freshwater Protozoa provides an extensive review of taxonomic information and detailed descriptions of 400 genera of Amoebae, Flagellata and Ciliata, all of which have a worldwide distribution.

A Beginners Guide to Freshwater Microscopic Life is a practical, spiral-bound guide written by David Seamer which offers a fantastic introduction to the multitude of microscopic organisms found in freshwater. For those with a more specific interest, An Illustrated Guide to the Freshwater Protozoa provides an extensive review of taxonomic information and detailed descriptions of 400 genera of Amoebae, Flagellata and Ciliata, all of which have a worldwide distribution.

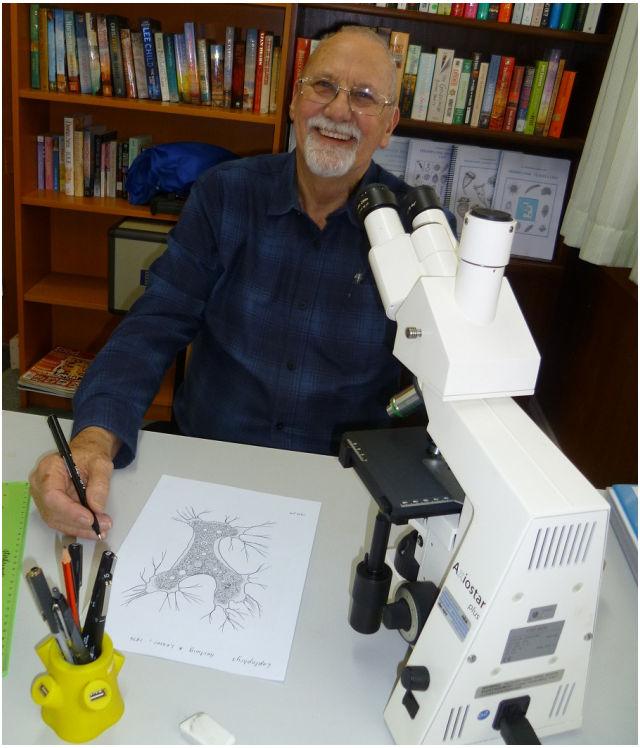

In 1993, David Seamer bought an old school bus and converted it into a mobile home and laboratory. He spent the next 20 years travelling around south-east Australia and Tasmania collecting, cataloguing and drawing the biodiversity of the micro-world. David has now settled in a county town in Australia where he has access to a great range of environments from semidesert springs to alpine ponds and lakes and continues to sketch, study and identify microscopic life.

In 1993, David Seamer bought an old school bus and converted it into a mobile home and laboratory. He spent the next 20 years travelling around south-east Australia and Tasmania collecting, cataloguing and drawing the biodiversity of the micro-world. David has now settled in a county town in Australia where he has access to a great range of environments from semidesert springs to alpine ponds and lakes and continues to sketch, study and identify microscopic life.

David took the time out of his busy schedule to discuss how he first got into studying microscopic life, the biggest challenges he’s had to overcome while creating these books and more.

Can you tell us about how you first developed an interest in studying microscopic life?

Ever since I was a small child, the natural world has fascinated me and my bedroom became a study place for caterpillars, tadpoles, lizards, insects of any description and anything else that I could keep in jars, boxes or old abandoned aquariums. But it wasn’t until I was about 15 and in high school that I discovered the micro-world, during a double biology lesson in which the teacher was using amoebas collected from a local pond as examples of an animal cell. While I was drawing an amoeba I noticed other ‘wigglers’ and drew them as well. After the lesson I approached the teacher and asked what these other things were. He pointed to a copy of Ward and Whipple’s Freshwater Biology and once I opened it and saw drawings of what I had seen, I was instantly hooked. I saved my money from a couple of lawn mowing jobs to buy my first microscope and it has become a lifelong passion ever since.

Which techniques would you advise a beginner in this field of study to use?

My advice to beginners is to be aware that these organisms are real creatures and should be treated with the same respect as any other animal. Collect your samples and examine them as soon as possible. Ideally, they should still be alive for once dead many of them decompose and break down very quickly. Preserved specimens often change shape and distort so live is always best. A good microscope is essential and the use of a measuring slide or an eye-piece micrometer, as well as phase contrast, is of great help. There are thousands of species so don’t try and identify organisms to that level. Genus or even family are as far down as one should go to start with.

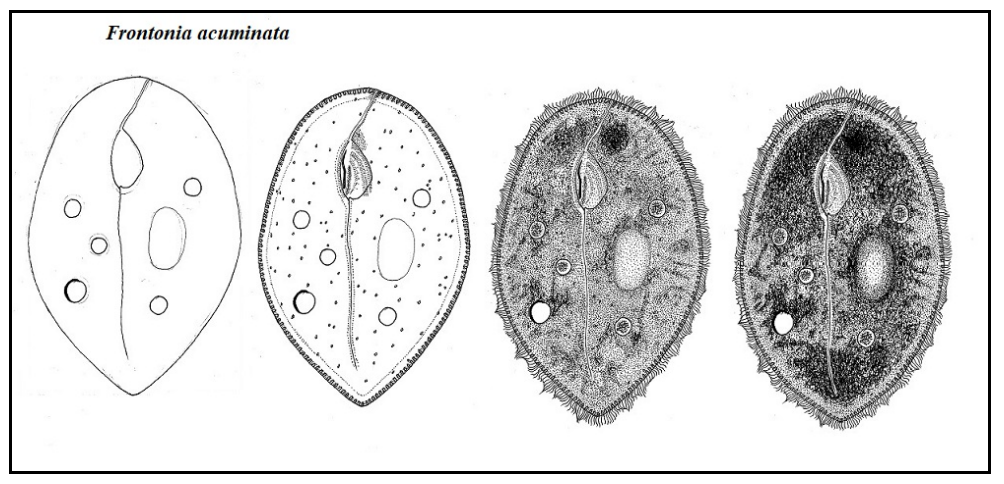

I found it really fascinating looking at your illustrations of microbes and the incredible detail you’ve included. Can you explain the process of drawing from live microscopic observations and the challenges of this method?

Drawing from life requires patience and lots of it. Starting with basic measurements to get proportions is the first step. This illustration (see above) is fairly typical of my technique. I draw the initial outline and basic details in 2B pencil and then when I am satisfied that all is correct, I use various grades of felt tipped pens to complete the drawing. Of course one must have knowledge of the subject so as to point out specific identification pointers.

What does your essential field kit include?

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide–mouth jars with screw on lids, and a notebook for the recording of date, location, temperature and any other variable details – all packing into a large knapsack type bag in case a bit of a hike is involved.

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide–mouth jars with screw on lids, and a notebook for the recording of date, location, temperature and any other variable details – all packing into a large knapsack type bag in case a bit of a hike is involved.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome while creating these books?

The biggest challenge one faces is reference material. It is essential to get not only the identification correct, but also the internal structure of these tiny organisms. Because taxonomy is constantly changing and developing, keeping up with name changes can be a challenge. While the internet can be invaluable, it is full of incorrect information and one must be very cautious when using it.

When I started out, I was constantly frustrated by not only the lack of availability of reference material on this subject but also the language. So many books were written by scientists for scientists, or were so simple that they were pretty well useless, that finally I decided to write a number of comparatively comprehensive but simple guides aimed at the amateur, student and enthusiast. These guides have proved quite popular and have currently been despatched to 50 countries around the world.

How have environmental changes as a result of climate change affected the distribution of and variation in microorganism species?

Environmental changes resulting from climate change affect the distribution and variation of microorganisms in very subtle ways. Whilst many species are incredibly robust, others are very delicate and can easily be affected by things like water temperature. Some protists need very specific environmental conditions in order to exist. Freshwater is a fluid (no pun intended) environment and every change has its ramifications. For example, droughts can obviously dry out ponds, streams and even small lakes as well as change the oxygen levels and pH of water bodies and this can result in a change in biodiversity. Likewise, floods will have the same effect with an increase in additional nutrients such as nitrates and phosphates from farmers’ paddocks causing algal blooms.

David Seamer has privately published his collection, two of which are available at www.nhbs.com/david-seamer