In the lead up to the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in November of this year, we are writing a series of articles looking at some of the toughest global climate crisis challenges that we are currently facing. This post looks at the evidence for and challenges posed by a global decline in insects.

What is the evidence for a global insect armageddon?

One of the first meta-analyses of insect population decline was published in 2014 by Dirzo et al. in Science under the title ‘Defaunation in the Anthropocene’. This seminal paper reported that 67% of monitored invertebrate populations showed 45% mean abundance decline and warned that ‘such animal declines will cascade onto ecosystem functioning and human well-being’. Three years later, Hallmann et al. (2017) published the results from 27 years of malaise trap monitoring in 63 natural protection areas in Germany, and concluded that insect biomass had declined by more than 75% during this time. This paper in particular was widely reported in the media, creating widespread concern among the public of an impending insect armageddon, or ‘insectageddon’.

Since then, several other reports have continued to draw attention to declines in insect abundance, biomass and diversity around the world (for excellent reviews see Wagner (2020) and Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhuys (2019)). However, many of these studies have been restricted to well-populated areas of the US and Europe and there is little information available to assess how these patterns compare with other less well studied regions.

Despite the abundance of data suggesting a pattern of global insect decline, many studies show conflicting results, with datasets from a similar area often reporting different patterns. There is also evidence that some insects are faring well, particularly in temperate areas which are now experiencing milder winters. Species that benefit from an association with humans, such as the European honeybee, may also be experiencing an advantage, along with certain freshwater insects that have benefited from efforts to reduce pollution in inland water bodies.

What are the challenges in assessing and predicting insect population trends?

In comparison to vertebrate groups, comprehensive long-term datasets are rare for invertebrates. This is primarily down to the fact that invertebrates are incredibly species rich and so, even for those that have been formally identified and described, a considerable amount of skill and knowledge is required for reliable identification. In addition to this high level of expertise is the need for large amounts of field equipment, which means that long-term, comprehensive studies can be expensive and difficult to fund.

Both historical and current invertebrate monitoring data tends to come from a small number of wealthy and well-populated countries (usually the US and western Europe), and there are comparatively few datasets available from tropical and less developed areas. Unfortunately, these understudied countries and regions tend to be the areas where we might expect to find the most diverse and species rich populations of invertebrates.

Other challenges relate to the way that data is collected. Using total insect biomass as a measure provides a useful large-scale perspective and provides information relevant to ecosystem function. It also minimises the problems involved with taxonomy and identification. However, using this measure means that species-level trends are completely overlooked.

What are the main stressors affecting insect populations globally?

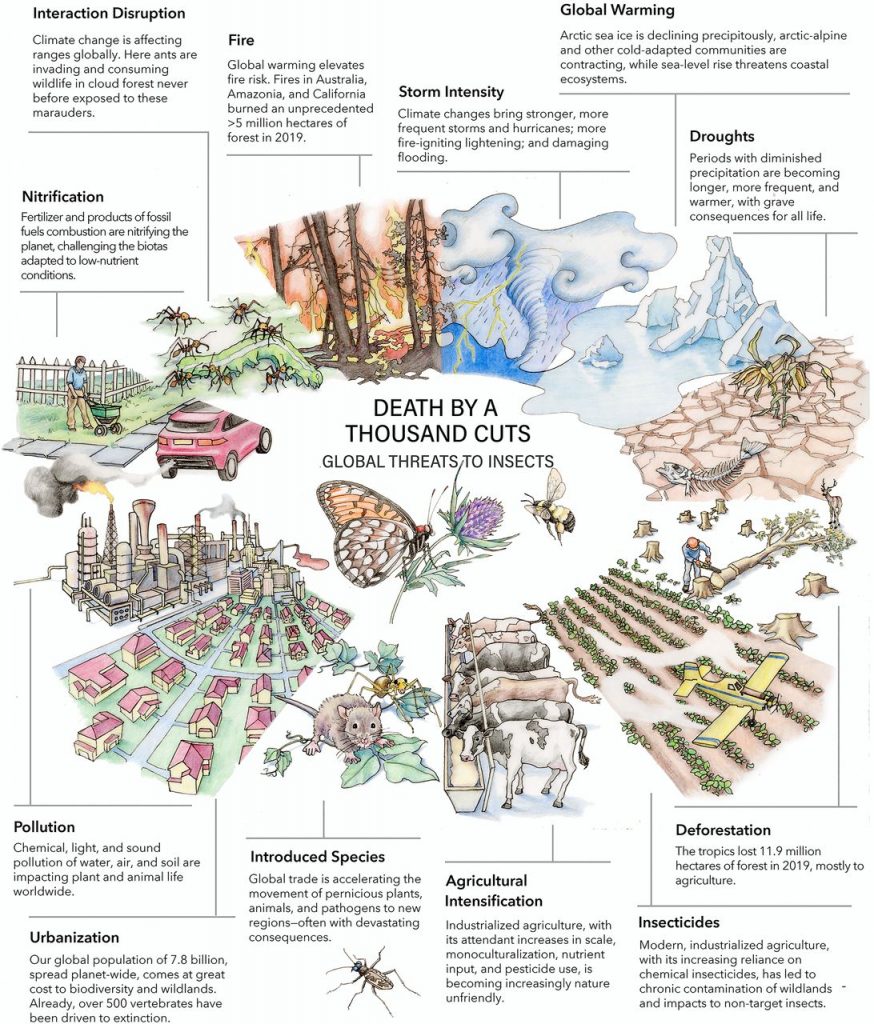

Studies suggest that the main stressors impacting invertebrates are changes in land-use (particularly deforestation), climate change, agriculture, introduced and invasive species, and increased nitrification and pollution. However, it is rare that a single factor is found to be responsible for monitored declines and the situation has been described as being akin to ‘death by a thousand cuts’.

In a recent special edition of PNAS, that looked in depth at the available research and literature on insect decline in the Anthropocene, climate change, habitat loss/degradation and agriculture emerged as the three most important stressors.

Where do we go from here?

Traditionally, conservation has focused on rare and endangered species. However, with mass extinctions and large scale invertebrate loss, which include declines in formerly abundant species, a different approach is required. Invertebrates form an important link between primary producers and the rest of the food chain, and play a key role in most ecosystems. They provide numerous ecosystem services such as pollination, weed and pest control, decomposition, soil formation and water purification, and so their fate is of both environmental and economic importance.

There are several things to be positive about within the realms of invertebrate conservation: over the past decade, funding to support insect conservation has been growing and, in many countries, there are now substantial grants allocated to monitoring and mitigation projects. The EU and US have seen widescale banning of certain pesticides following research demonstrating their impacts on both economically important pollinators and other fauna. Finally, citizen science projects to study invertebrate populations are becoming both numerous and successful, greatly increasing the amount of comprehensive, long-term data that is available to inform conservation decisions.

Despite this, much more long-term data on invertebrate populations is required, particularly from regions outside of Europe and the US, such as tropical areas of the Americas, Africa and Asia. Attention to factors such as the standardisation of survey techniques and improved data storage and accessibility are also important, as well as the utilisation of new methods including automated sampling/counting equipment and molecular techniques. Using the information available, evidence-based plans for mitigating and reversing declines are desperately required.

All of this takes time however, and we need to act now. Even without comprehensive species-level data, we know that a biodiversity crisis is occurring at a rate serious enough for it to have been termed the ‘6th Mass Extinction’. Individual, group, nationwide and global action will all be required to combat this. Widescale change in societal attitudes to insects will undoubtedly need to play a role in this process, alongside global efforts to slow climate change and develop insect-friendly methods of agriculture.

Summary

• Numerous studies have reported large-scale declines in insect populations, with several estimating a loss of approximately 1–2% of species each year.

• The availability of high-quality and long-term datasets is a limiting factor in assessing population trends. Furthermore, available data tends to be from well-populated and historically wealthy areas such as the US and western Europe, with the diverse and species-rich tropics severely under-researched.

• The main stressors thought to be impacting insect populations globally are climate change, habitat loss/degradation and agriculture. In most, if not all of these cases, a combination of these and other factors are likely to play a role.

• Although there are some aspects of insect conservation to be positive about, much work still needs to be done. Further monitoring and recording are required, particularly in poorly studies areas, in order to inform conservation decisions. Simultaneously, local and global efforts must be made to slow climate change, halt the destruction of ecologically important habitats and develop nature-compatible methods of agriculture.

References and further reading

• Jarvis, B. (2018) The Insect Apocalypse is Here. The New York Times

• Dirzo, R. et al. (2014) Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345: 401–406

• Hallmann, C. A. et al. (2017) More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One 12: e0185809

• Wagner, D. L. (2020) Insect declines in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65: 457–480

• Sánchez-Bayo, F. & Wyckhuys, K. A. G. (2019) Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 232: 8–27

• Wagner, D. L. et al. (2021) Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118(2): e2023989118

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse

Eye-opening, inspiring and riveting, Silent Earth is part love letter to the insect world, part elegy, part rousing manifesto for a greener planet. It is a call to arms for profound change at every level – in government policy, agriculture, industry and in our own homes and gardens, to prevent insect decline. Read our extended review.

The Insect Crisis: The Fall of the Tiny Empires that Run the World

The Insect Crisis: The Fall of the Tiny Empires that Run the World

In a compelling global investigation, Milman speaks to those studying this catastrophe and asks why these extraordinary creatures are disappearing. Part warning, part celebration of the incredible variety of insects, The Insect Crisis highlights why we need to wake up to this impending environmental disaster.

Climate Change and British Wildlife

Climate Change and British Wildlife

In this latest volume in the British Wildlife Collection, Trevor Beebee examines the story so far for our species and their ecosystems, and considers how they may respond in the future. Check out our interview with Beebee, where we discuss the background of this book, his thoughts on conservation and his hopes for the future.

Rebugging the Planet: The Remarkable Things that Insects (and Other Invertebrates) Do – Any Why We Need to Love Them More

Rebugging the Planet: The Remarkable Things that Insects (and Other Invertebrates) Do – Any Why We Need to Love Them More

Environmental campaigner Vicki Hird demonstrates how insects and other invertebrates, such as worms and spiders, are the cornerstone of our ecosystems and argues passionately that we must turn the tide on this dramatic bug decline.

The Last Butterflies: A Scientist’s Quest to Save a Rare and Vanishing Creature

The Last Butterflies: A Scientist’s Quest to Save a Rare and Vanishing Creature

Weaving a vivid and personal narrative, Haddad illustrates the race against time to reverse the decline of six butterfly species. A moving account of extinction, recovery, and hope, The Last Butterflies demonstrates the great value of these beautiful insects to science, conservation, and people.

Why Every Fly Counts: Values and Endangerment of Insects

Hans-Dietrich Reckhaus discusses the beneficial and harmful effects of insects and explains their development and significance for biodiversity. This second, fully reviewed and enlarged edition provides new insights into the value of species seen as pests, insect development and their decline in different regions in the world.