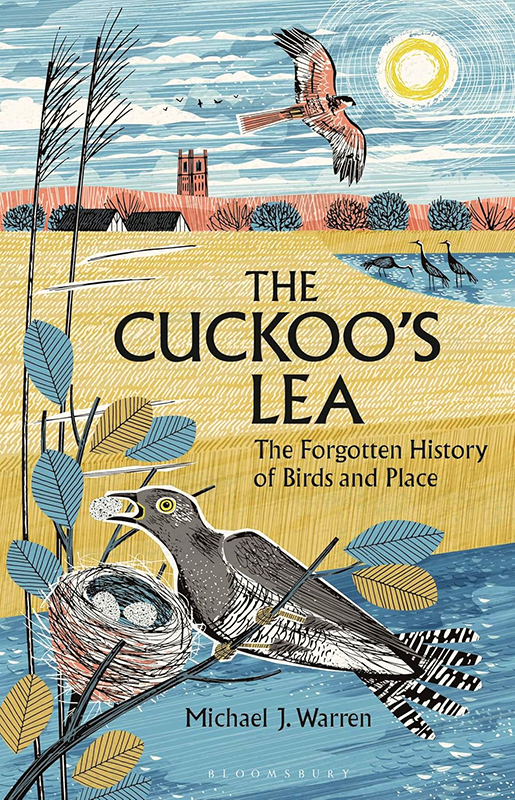

Weaving together early literature, history and ornithology, The Cuckoo’s Lea takes the reader on a journey into the past to contemplate the nature and heritage of ancient landscapes. It explores the stories behind our placenames, alongside historical accounts of bird encounters thousands of years ago, their hidden secrets, the nature of places and more.

Weaving together early literature, history and ornithology, The Cuckoo’s Lea takes the reader on a journey into the past to contemplate the nature and heritage of ancient landscapes. It explores the stories behind our placenames, alongside historical accounts of bird encounters thousands of years ago, their hidden secrets, the nature of places and more.

Michael J. Warren is a naturalist and nature writing author who teaches English at a school in Chelmsford. He was an honorary research fellow at Birbeck Colledge, curates The Birds and Place Project, and is a series editor of Medieval Ecocriticisms. We recently had the opportunity to speak to Michael about The Cuckoo’s Lea, including how he first became interested in birding, what he discovered throughout his research for this book and more.

Michael J. Warren is a naturalist and nature writing author who teaches English at a school in Chelmsford. He was an honorary research fellow at Birbeck Colledge, curates The Birds and Place Project, and is a series editor of Medieval Ecocriticisms. We recently had the opportunity to speak to Michael about The Cuckoo’s Lea, including how he first became interested in birding, what he discovered throughout his research for this book and more.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about yourself, and how you became interested in birds and birding?

Professionally I do many different things, but birds, the natural world, conservation and environmentalism are central to all of it. I’m an English school teacher as well as an academic working in the environmental humanities (my PhD was on birds in medieval poetry), so literature, language and history are always intertwined with my love of nature and nature writing. I was formerly chair of the New Networks for Nature group and am currently a trustee for the charity Curlew Action, where I advise on education as it relates to the forthcoming Natural History GCSE.

I’ve been into birds and birding for as long as I can remember, having been encouraged by my uncle and aunt who are both keen naturalists themselves, but most of all I was inspired by my parents as they did one of the best things I think any parent can do for a child – they educated me in the great outdoors. By which, I meant that all our holidays were in various wild locations across the UK, involving ramshackle cottages in remote valleys and by secluded rivers, from which my brothers and I were free to roam, exploring and playing each morning. I have a deep passion for British landscapes and wildlife, and I am who I am today because of those early experiences. They shaped me profoundly, and I’m now trying to do the same with my two daughters (which is working so far, but they’re still young and impressionable right now!)

What inspired you to write a book on the history of place names with avian origins?

Initially this idea came from my academic research on birds in medieval literature and culture. When I started to explore the presence of bird species in place names – in the realm of medieval studies by default as most English place names are Old English in origin and can be traced back to the Middle Ages – I was astounded by just how many there were. I knew there was something really fascinating to examine, including what these names could tell us about people’s ecological knowledge and relationships over one thousand years ago. Every name is a story.

One of my reviewers has kindly described The Cuckoo’s Lea as a ‘Rosetta stone for our ecological knowledge’, but it’s the place-names that are the stone. They provide us with a portal into the imagination of early people who were encountering and interacting with these environments. I realised that placenames were the perfect subject for my first narrative nonfiction book as it combines birds, landscapes, medieval history and ecological history, while also providing the opportunity for me to travel to different places, experience them first hand, and collate all these elements into a personal narrative with broad appeal.

Each chapter focuses on a different location and species across the UK. How did you decide which areas to focus on and which of the many species that reside there to highlight?

I went back to the drawing board a lot with that one!

I wrote this book alongside becoming a father: six years of raising two daughters through those early years combined with six years of research, travel, and writing at 4am in the morning because that was the only way to carve out writing time until I got my book deal with Bloomsbury. As such, practicality determined a lot of it – I travelled to locations I could feasibly reach within my budget (at one point we were living on my part-time salary and my wife’s statutory maternity pay) and the restricted time available. Under other circumstances I would have liked to have travelled farther afield for the book – to Ireland, for instance.

My selection was also determined by the range of species that I thought would most appeal to readers. So, although there’s a danger of over-featuring certain birds in nature writing, I knew I had to include cuckoos, cranes and nightingales in the book because everyone loves them! These three species were also popular in medieval culture too, so it made sense to feature them, and I lived in Cranbrook (Kent) for most of the time I was writing the book, so that provided an obvious starting point.

I also thought hard about the range of ideas I wanted to explore relating to how birds evoke and define place for us and allowed this to lead me towards particular birds and/or places. For instance, I wanted to write about the soundscape of birds as a phenomenon that both animates or shapes place – a recurring idea in the book. This meant that owls became important as, to me, they exemplify this enthralling idea that our ancestors naturally and happily recognised bioacoustics as distinguishing properties of a place’s atmosphere. Finally, and again practically, it was also imperative to have some geographical range to my adventures so any reader would be able to read about somewhere in their home county or a nearby county.

What was the most surprising discovery you made whilst researching this book?

I think it was the sheer number of species represented in Old English placenames.

I don’t think you would expect birds to turn up so frequently in placenames, given that you’d want a place-marker or identifier to be reliably solid, present and static – and birds don’t tend to remain static much of the time. Some of the species that can be found in our placenames, such as swallows and cuckoos, aren’t even in Britain for much of the year! On this basis, wrens, buntings, snipe, dunnocks and sparrows aren’t species I expected to find.

There’s also nowhere that really matches the range of species in English placenames. Gaelic does have a good range across both Ireland and Scotland, but it’s difficult to trace the origins of the names beyond the 19th or 18th centuries as the cultures were oral, so names often weren’t recorded until the first OS maps were produced.

On the flip side, I was also surprised by the species that aren’t in our place-names – nightingales, for instance. This species was highly prominent and celebrated in both medieval art and poetry, and would have been much more populous than they are today, so how is it that they didn’t find their way into placenames? (That doesn’t stop me having a chapter on nightingales, by the way.) The same goes for corncrakes. There was an Old English name for the bird, and their calls would have undoubtedly been an unavoidable and loud sound of summer throughout the land. Herons only appear once or twice, and, perhaps most surprisingly, the robin (or ruddock in Old English) doesn’t feature at all!

Finally, can you tell us what you’re working on at the moment?

Right now, I’m focused on making a success of The Cuckoo’s Lea!

Alongside booking readings, signings and talks, I’m also creating a website titled The Birds and Place Project (birdsandplace.co.uk) which aims to record the birdsong of all the species mentioned in English placenames – which is quite an undertaking! It will be a lifelong project as I’d like to extend it beyond England and the English language to include other countries and languages found across Britain and Ireland. I see it as an extension of my book; and as a site for anyone to find out about this fascinating, but currently little-known, aspect of our natural history and heritage.

Beyond that, I’ve got my eye on my second book, provisionally titled Hibernal: The Obsessions of a Justified Winter Lover. I’m a serious winter fanatic, so I’ve known for some time that my second book will be a meditation on my favourite season. It will be an emotional and personal journey into my obsession with winter, including encounters with those living and surviving the season in the far north, as well as those who can’t stand winter and suffer terribly in the darkness and cold. Plus, it will highlight historical stories about the importance of winter, how previous times and cultures coped with it, and discuss how winter as a season is changing because of climate change. I don’t think there’s much chance of me commencing this book in 2025, but then again, if this book is going to take me another six years, I can’t waste a single winter…

The Cuckoo’s Lea is available here