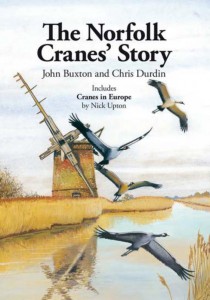

Horsey Estate, in Norfolk, has, since 1979, been home to a colony of resident, and eventually breeding, Common Cranes. John Buxton has been resident on the estate a little longer, and was perhaps the perfect host to his surprise new neighbours…

Horsey Estate, in Norfolk, has, since 1979, been home to a colony of resident, and eventually breeding, Common Cranes. John Buxton has been resident on the estate a little longer, and was perhaps the perfect host to his surprise new neighbours…

What a fascinating story – how did you feel when you first heard that there were cranes resident in Norfolk, on the Horsey Estate? What do you think attracted them to the site?

In October ’79 I was delighted when Frank Starling, the grazing tenant, had reported he had just seen “the 2 biggest bloody herons” on the marshes on which he grazed his cattle. The attraction to the cranes was a combination of a quiet, undisturbed area of wetland and a plentiful supply of food in the form of unharvested potatoes. Both sites were within the Horsey Estate area.

How did the writing of the book come about? What brought you two together and why now?

For the first few years I tried to keep the presence and nesting activity as quiet as possible but I felt the story would have to come out eventually. I was worried that inaccuracies would begin to creep in because various interested people were longing to report facts as they saw them. I wrote down careful notes about the cranes’ activities and as I learnt more about them and their habits I realised that at some stage in the future, I should recall the true story as it happened. Chris Durdin was given a sabbatical period while still employed by the RSPB in 2009 to gather and write down the facts as told by me from my notes and diaries I had kept about the cranes over the last 20 years. The work became delayed for various reasons but finally, in 2011, it simply had to be completed.

The first part of the book follows the cranes and their efforts (sometimes exhausting!) to breed year by year from 1979 to 2010. How was 2011 for them?

2011 was a fairly unsuccessful breeding summer for the cranes at Horsey, one pair definitely hatched young by my observations of their activity from a fixed hide at 200 metres. I could not see the young in fast growing reed but could observe the parents by their tall necks showing above those reeds. I was aware also that the young only survived a few days and I witnessed a male marsh harrier, which had nested only 50 yards away from the cranes’ nest, carrying a small gold creature as prey, which he took to feed his young. Another pair of cranes in a different site within the Horsey Estate also failed to raise any young.

What was it like revisiting the history of the years from 1979 – particularly going back through all the notebooks?

It was quite revealing to catch up with my notes, which acted usefully as a reminder of the facts over 30 years. Thanks to Chris Durdin’s patience, we finally achieved the publishing of the book.

The Norfolk cranes are grus grus, or Common Crane, and the book is full of observations on crane behaviour. The word ‘tenacity’ is used in the book to describe these birds and their endless attempts at sucessful breeding. How would you sum up the typical crane personality?

Like all individuals of a species, cranes vary in personality, I have observed particular traits in quite a few individuals, which I had got to know fairly intimately from fixed hides. The females are undoubtedly the best parents, with remarkable tenacity and sense of duty at the incubation and subsequent caring for chicks. The males are usually less reliable in their duties. Incubation is normally shared but I have seen many examples of the male going walkabout when he should be sitting on the eggs. This can be fatal if we have late frosts in May. One particular pair have only hatched young once in 4 years of nesting attempts.

What has been the cranes’ legacy in terms of their effect on your life experience, personally and professionally?

The cranes establishing themselves in Broadland, after a break of 400 years, is a major event in UK bird conservation. It has kept me extremely busy, looking after them for 30 years and although my son, Robin, since 2000 is now the lessee of the Horsey Estate from the National Trust, I am acting as his reserve warden. A job which he would never have had time to undertake as a busy, self-employed land agent. My present age is 83 and I am extremely lucky to be able to both physically cope with wardening the Horsey reserve and still enthusiastically enjoy photographing wildlife in high definition video and digital imaging with a still camera.

As far as I am personally concerned, with a wonderful wife and family around as backup, I am as fully occupied as I have ever been, doing things I enjoy with great enthusiasm.

I am hugely relieved that the book has been published at last and deeply grateful to Chris in particular, and among others, Nick Upton, for his invaluable contribution and chapter about cranes in Europe.

Chris Durdin worked for the RSPB for 30 years and was in the Norwich office while the cranes were establishing themselves…

Chris, how did you become involved with the cranes?

Not long after I arrived at the RSPB’s Norwich office, I was told in confidence about the nesting cranes and asked to help in several ways, including some shifts watching a nest in the spring of 1982. Regular contact with John continued, but it wasn’t hands-on as he and Bridget looked after the RSPB contract wardens who helped at Horsey for several years.

You were in charge for a time of deflecting public and media interest in the cranes at the RSPB office – what was it like trying to keep the cranes secret?

It helped that there was a rumour in the birdwatching world that the cranes had escaped from captivity, so on that basis they didn’t really count as wild birds. We didn’t discourage that perception, which lessened the pressure and risk of disturbance to nesting birds in spring and summer. They were fairly easy to see in autumn and winter from the coast road, so it was easy enough to encourage birdwatchers to look then. Of course there were well-informed birdwatchers and media, especially after juvenile cranes that were clearly recently fledged started to appear. Those in the know seemed to accept the need for care with this privileged information, though naturally some keener media were referred to John, who batted queries into the long grass.

How does the Norfolk Cranes’ story fit in the context of current conservation issues and efforts in the UK today, and how could organisations and government best serve the potential future of cranes in the UK?

We can start by remembering that they disappeared from the UK as breeding birds some 400 years ago due to a combination of hunting and wetland loss. So no hunting and lots of big wetlands are obvious messages – all the British birds are on large, protected wetlands, mostly nature reserves. That this includes a re-created wetland at RSPB Lakenheath Fen is particularly encouraging. Cranes are big, talismanic birds, and we hope they are an easy-to-grasp way of showing the value of wetland protection and creation to the public and to Government. Cranes have a preference for large, undisturbed wetlands, so they are also a reminder of the value of large-scale habitat protection and restoration.

So, can we expect our skies to be full of cranes in the near future?

No, but they should be a more familiar part of the scene in small numbers in a few areas. It’s taken more than 30 years to go from their natural re-colonisation at Horsey to about a dozen pairs in Eastern England, so we all need great patience. An exception to that is if you’re lucky enough to live where the process is being speeded up in SW England, where cranes are being reintroduced in Somerset. While we hope the spread will accelerate, probably boosted by more immigrants from the expanding – in both numbers and range – European population, cranes will probably never be common, given their preference for large wetlands.

If you’d like to see skies full of cranes, the answer is to go where they form flocks in several parts of Europe. One of the best places to go is Extremadura in Spain where up to 100,000 cranes over-winter. I will be there with Honeyguide Wildlife Holidays in February 2012!