Behind More Binoculars: Interviews with Acclaimed Birdwatchers is the second book of interviews with birders. They are chosen to encompass a varied range of perspectives and approaches to birding.

Behind More Binoculars: Interviews with Acclaimed Birdwatchers is the second book of interviews with birders. They are chosen to encompass a varied range of perspectives and approaches to birding.

We caught up with the authors, Keith Betton and Mark Avery, to ask them some questions about this insightful, humorous, thought-provoking and thoroughly unique approach to getting to the core of what makes birders tick.

Many of the interviewees’ route into birding was roaming the countryside near their homes during their childhood, often in rural locations. With parents now reluctant to let their children stray and wild spaces less common, do you think this presents a problem and if so, what is the best route now for children to discover and connect with the natural world?

Keith: I do see this as a problem for many young people who want to experience nature. Also, it is now more complicated for schools to organise nature rambles because of the health and safety checks that need to be made. There are still great local groups organised by RSPB Wildlife Explorers and some of the Wildlife Trusts – but just going out on your own is no longer an easy option.

Mark: It is a bit of a problem – but arguably the problem is in the parents’ heads. Looking back, I think I was a bit too cautious with my children and I was a lot less cautious than many parents. It is to do with what is normal – when I was a kid I headed out into the countryside all day and apart from a few bruises and grazes never came to any harm, but very few children get that delicious freedom these days.

I was encouraged that so many birders end up working in wildlife/conservation. What do you think inspires a young birder to move into conservation and not just focus on birds?

Keith: This is more a question for Mark I think. But they need to have passion for the bigger picture of conservation and not be thinking about earning much money.

Mark: Doing something that you feel is worthwhile and working with kindred spirits is a great way to spend your working life. You spend a lot of time at work – why not get a real kick out of it!

As the title suggests, all the interviewees were using binoculars and telescopes from quite an early age. I had binoculars from an early age (ostensibly for plane-spotting) but preferred to use my normal sight. Is it possible to be a birder without binoculars? Can you think of the gains and losses from using the naked eye instead of magnification?

As the title suggests, all the interviewees were using binoculars and telescopes from quite an early age. I had binoculars from an early age (ostensibly for plane-spotting) but preferred to use my normal sight. Is it possible to be a birder without binoculars? Can you think of the gains and losses from using the naked eye instead of magnification?

Keith: The likes of Gilbert White in the 1700s made do without binoculars as they had not been invented, but today they are easy to obtain and don’t have to cost a fortune. Using all of your senses to detect nature is important, but unless you can see the details of the plumage you are missing out on so much.

Mark: Ears are important too. I’ve sometimes recorded how many species I detect and identify by sound before sight and it’s usually about 40% of them on a walk around my local area. Being attuned to nature comes with time. I have been walking down a busy noisy street in London and heard a bird call way above my head (often a Grey Wagtail – a bird with a loud simple flight call) and looked up to see it. No-one else paid it any attention of course. If I’d seen anyone else looking up I’d have known they were birders.

There is lots of travelling in this book; I’m going to avoid the obvious question regarding carbon footprint and concentrate on the positive. Jon Hornbuckle’s alarmingly dangerous travel adventures also resulted in him helping protect endangered birds and forests in Peru. What are the benefits travelling birders can bring to the birding and conservation movements?

Keith: If there were no people watching birds and wildlife in many of the world’s national parks then I think a significant number would be turned over to agriculture. If we all travelled everywhere the world’s carbon emissions would increase to the extent that climate change would accelerate further. But if birders travel to conservation areas then the local people have a reason to want those areas to be saved.

Mark: No, the obvious question is the best one. Why do nature lovers travel so much when they know it harms nature? Beats me!

In the ‘Last Thoughts’ chapter of the book you mention that the demographic for birders is rather mature and mainly men. You claim this gender balance is improving and bearing that in mind, what do you think a similar book to yours would look like in twenty years time?

Keith: While the gender imbalance is shifting I doubt it will ever reach 50/50, so such a book would probably still contain more accounts from males than females. The average age in both of our books was around 50-60, and partly that’s because you want to talk about what people have done in the past – and older people have more stories to tell. But it would be good to move that average age down a bit!

Mark: I think the differences in birding and nature conservation in 20 years’ time will be more interesting than the gender of who is talking about them. But I hope and expect a more even gender balance.

There was often some discussion about ‘boots on the ground’ verses ‘reports and research’ approach to birds and conservation. What are your thought about the right balance between meetings, media and marketing strategies verses getting your hands dirty in ‘the field’?

There was often some discussion about ‘boots on the ground’ verses ‘reports and research’ approach to birds and conservation. What are your thought about the right balance between meetings, media and marketing strategies verses getting your hands dirty in ‘the field’?

Keith: You need both – but the danger is that too much money can be devoted to discussing a conservation plan and then not enough to make the plan happen. One of my biggest concerns is the obsession with safety audits before even a simple action. I was really struck by Roy Dennis’s account of being at an Osprey nest tree that was at risk of falling down and just needed a few nails and strips of timber to keep it in place. None of the staff sent to inspect it could fix the tree as there had not been a full safety audit, so Roy just climbed up and did it himself. That’s boots on the ground (well boots on the tree actually!).

Mark: Conservation needs both. I started as a scientist working in the field – and loved it. But if you work for an organisation, and you rise up the hierarchy, you are going to spend more time wearing a tie, sitting in meetings and less in the rain with sore feet. We really do need people with a wide variety of skills to change the world. I do think though, well I would wouldn’t I, that having some senior people who have come through the ranks and know what it is like out in the field and at the base of the organisation is a good thing?

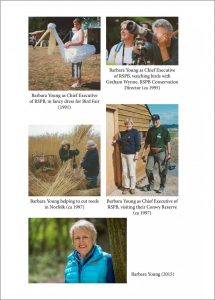

I really enjoyed Barbara Young’s interview, she had so much energy and conviction. I imagine her strident views and no-nonsense approach shook a few people up and she was convinced that nature conservation is a political issue. Do you agree – should nature conservation be more political, should birders and anglers for example see common ground, put differences aside and be a stronger political voice – should they even back a political party which shares their values or is that too far a step? If it is too far a step, how do you think the voice of birders and conservationists can be heard in the modern media blizzard that everyone is subjected to?

Keith: I’ll let Mark answer

Mark: Nature conservation is self-evidently political because it depends on altering people’s behaviour (and often they don’t want to change). You can’t increase Skylark numbers much without influencing hundreds or thousands of farmers. It’s difficult to talk to them all and persuade them to farm differently, but a change in incentives or legal requirements can get to lots of them. And that’s politics! Whether you use a stick or a carrot is politics. I don’t for a moment claim that birdwatchers must be political, but nature conservationists have to influence politics to have much impact. And the organisations to which we pay our subscriptions have to do a better job, as came out in a couple of interviews, at making that case. I don’t think that birders and anglers have completely overlapping views, but they do have partly overlapping needs – and that’s why they should work closer together on some issues (even if they fight like cats on others).

I can see why searching for rarities would be so addictive and many of the interviewees are very keen on recording them: what rarities do you expect to see turning up on these shores and which birds might go from rare to common in the UK over the next ten years?

Keith: Already in the last ten years my main birding area (Hampshire) has lost Yellow Wagtail and Tree Sparrow as a breeding species, and soon we may lose Willow Tit and Wood Warbler. We are likely to gain Great White Egret and Cattle Egret as breeders in the next ten years. As for real vagrants I think we’ll just keep getting a few new ones, although species that are declining in Europe (such as Aquatic Warbler) will turn up much less often.

Mark: Experience shows that we aren’t very good at getting these guesses right! Pass!

My final question maybe should have been my first, but can you tell me what inspired you to start interviewing birders in the first place?

Keith: It struck me that some of the real trailblazers of ornithology (such as Phil Hollom) were not going to be able to share their stories for much longer and so I sat down and got him to tell me about his life. Mark had a similar idea and came up with the idea for Behind the Binoculars. He wanted to interview me for the book. I agreed, and as it was still an early idea I suggested some other people who might be interesting to interview. In the end we realised we both had lots of ideas, and we agreed to work as a team.

Mark: They are interesting – sometimes peculiar, sometimes inspirational but interesting all the same.

About the authors

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.

Dr Mark Avery, many moons ago, worked for the RSPB and for 13 years was its Conservation Director. He is now a writer, blogger and environmental campaigner and is prominent in the discussions over the future of driven grouse shooting in the UK.

Behind More Binoculars: Interviews with Acclaimed Birdwatchers is available to order from NHBS

Signed Copies Available

NHBS attended the recent BTO Conference and Keith has kindly signed some stock of Behind More Binoculars; we have a very limited stock, so should you order, please state ‘signed copy’ in the comments and we will do our best. If you want to catch up on the first volume of interviews we currently have a special offer on the hardback edition.

From all of us at NHBS, we wish you plenty of happy and successful birding adventures in 2018.